Author order is crucial; it is the currency of academia. Within STEM disciplines, women and gender minorities, BIPOC scientists, and junior researchers consistently receive less credit for their knowledge production. Recognizing that the stakes of authorship and author order are high for CLEAR members, we have developed an approach to author order that emphasizes process and equity, rather than rules and equality.

This video, from the series Laboratory Life, shows the process:

We’ve also published a paper on our Equity in Author Order Protocol that details the processes more fully (please cite this paper, rather than the video, if you use this method).

CLEAR’s author order process

Our process is premised on a few important components:

First, we decide author order by consensus. Consensus-based decision making means that everyone agrees to the entire order, even if that agreement includes some unevenness. We explain how we do consensus-based decision making in our post on how we run lab meetings.

Secondly, we have our meeting about author order with the entire lab, including people who are not authors on the paper. This is part of how we do accountability, especially in terms of how the lab’s director or principle investigator has power over others in the lab. It also allows lab members to support their peers who may be overly modest.

Throughout, we aim to foster a process characterized by humility, accountability, collegiality, and good land relations, our lab’s main values.

Step 1: The spirit of the paper

All articles and their projects are different. Some are characterized by massive data wrangling, others by community-based collaboration. This means the same type of labour, such as statistics or communication with communities, will have different importance in different projects. We can’t always say doing statistics is worth 10 points of labour if sometimes those statistics are a key part of what makes the paper unique, important, and informative while other times statistics is just one more layer of icing on a cake. Discussing the spirit of the paper highlights what makes this project, this publication unique, important, amazing, and what makes it work.

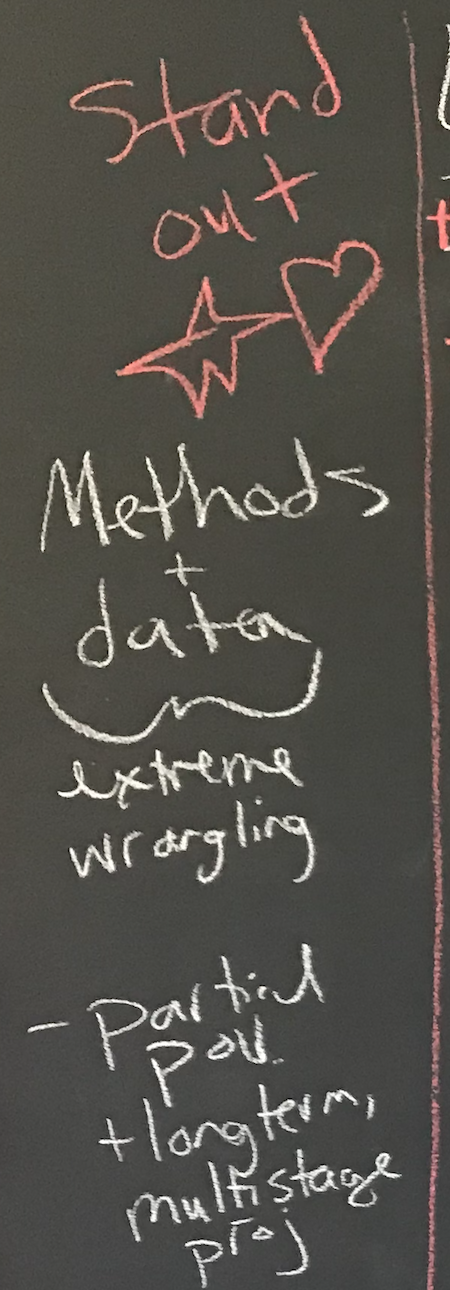

In this particular paper, the spirit of the paper is characterized by “extreme data wrangling” and the long-term perspective required to keep all the data straight (it was a paper that highlighted all plastic pollution research–quant and qual– in a region from the 1970s to the 2020s, which took over five years to write).

Step 2: Types of labour

Next, we make a list of allllllll the types of work that produced value for the lab. Statistics and gathering samples, writing and editing–but also emotional labour that held collaborations together, organizing meetings, administrating grants and payments, and staying in good relations with community partners and collaborators. Then, we highlight which of the types of labour on this list were essential to the spirit of the paper. We often rank these, or mark them in some way (via consensus) to show the key types of work that this project needed to be the type of project it is (spirit of the project). This sets us up for the future step of ranking people who did this kind of labour in higher positions than those that did labour that was less essential to the spirit of the project.

Here are some of the types of labour that happen in most of our projects:

- Gathering samples

- Maintaining contamination controls (aka cleaning)

- Organizing meetings to discuss the paper

- Taking over tasks so others can go home sick or for those that need a break

- Facilitating difficult conversations

- Teaching skills and mentoring methodologies/collaborations

- Being a good listener and paraphraser in the process of research design or editing, which impacts the clarity of the research

- Providing emotional labour

- Doing administrative tasks, such as ordering supplies, making sure hours are logged, or scheduling lab times

- Doing accountability tasks such as ensuring ethics and permits are in place and up to date

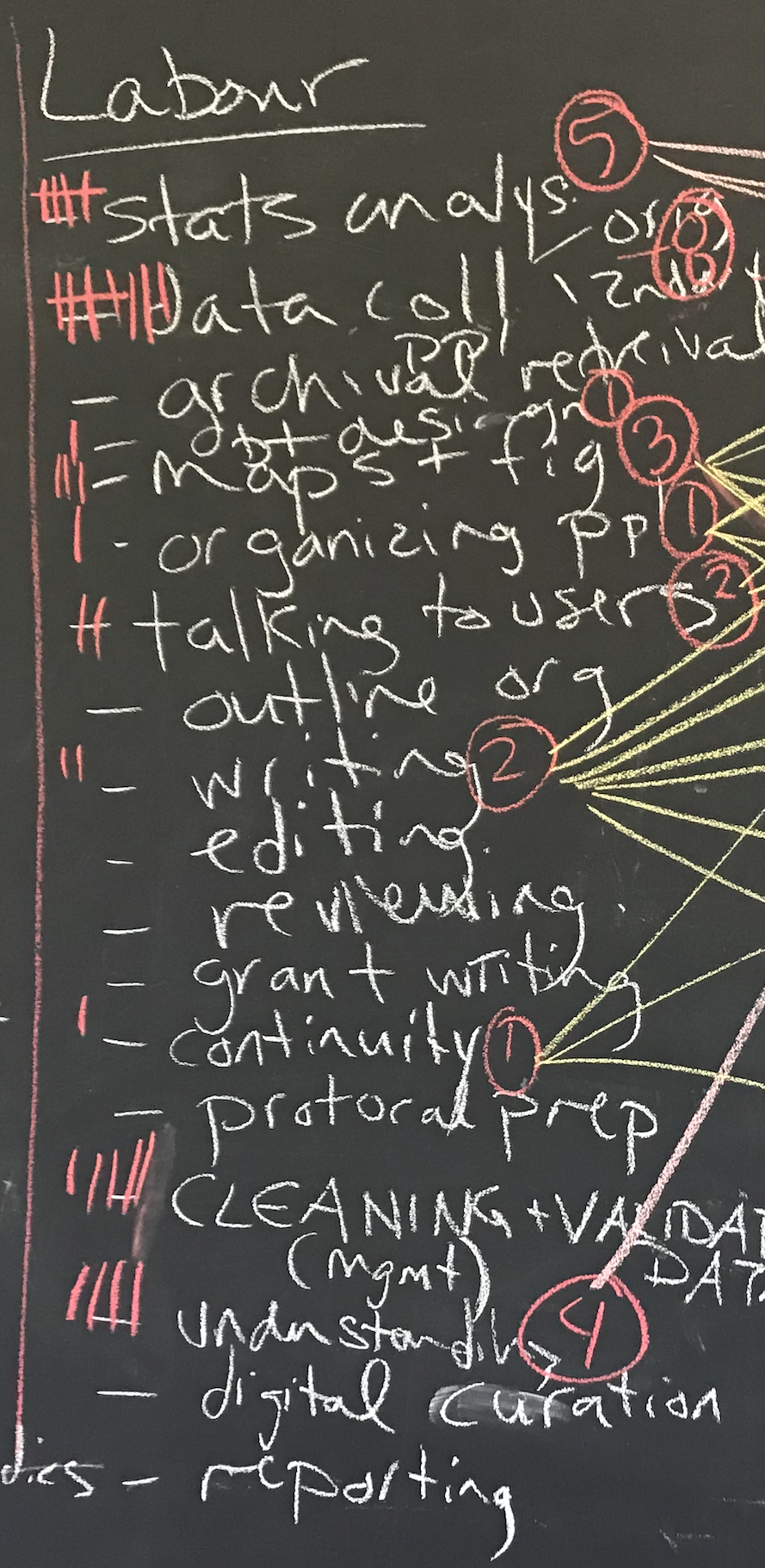

In this project, the forms of labour that were the most important (designated by the red hash marks on the left of the list) are data collection, stats analysis, cleaning and validating the data, and understanding the data. You can see other forms of labour like archiving, database design, organizing people, grant writing, writing, maps and figures, etc as other forms of labour. In the paper we did after this one, the spirit of the paper was about accountability (it was a paper about colonial pollution research in Inuit homelands), so one of the most important forms of labour was obtaining permits and permissions from different Inuit governing groups, and staying in contact with them.

Step 3: Who worked on this?

Then, we make a list of alllllll the people who did those forms of labour. Some of these people are obvious, but sometimes people who do care work, community work, emotional labour, administrative work, organizational work (all the gendered types of work!) are left out of what is often thought of as “scientific labour.” Our process brings these people in. In our case, this step is essential to equity, humility, and accountability.

Step 3: Who did what?

In this step, we match up people to their labour. Usually we have all of this on a blackboard and draw lines between the list of people and the list of labour. Many people have multiple lines. We get people to say what they did, but others in the lab are also expected to remember and speak up for the work people did that they might take for granted. This is especially important for gendered work and how it is often assumed to be innate to personality rather than a form of labour (for example, experts in collaboration techniques are seen as “friendly and organized” people rather than as experts).

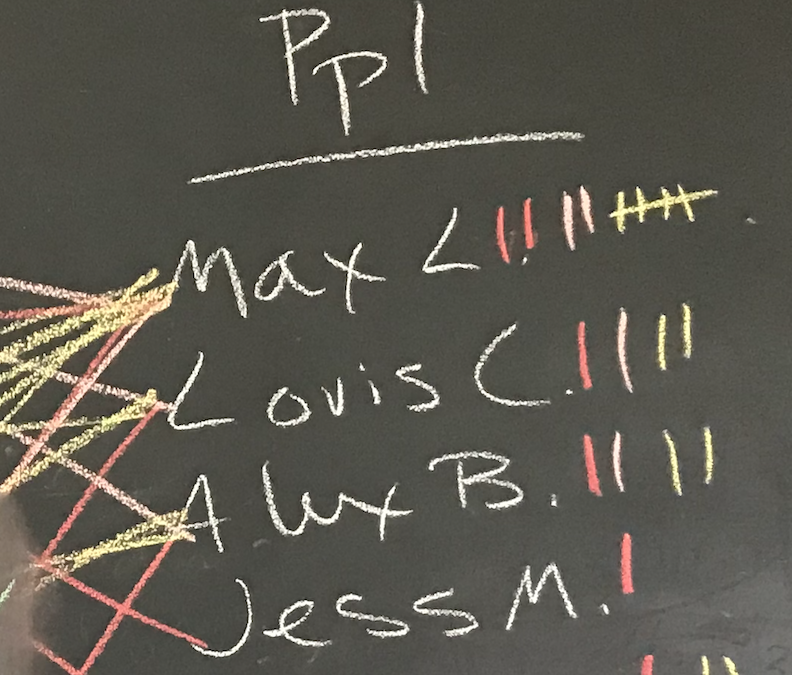

Here, four people did a lot of labour. You can see all the lines to their names from different forms of labour on the left, and on the right there are different coloured hash marks. The red hashmarks are for the most important types of labour (the labour that gave the project its unique spirit). The coral/pink marks are for fairly important types of labour, and the yellow ones for the least important forms of labour. You can see that clusters (step 4) are already starting to emerge: Louis and Alex will be in the same cluster.

Step 4: Clusters emerge

When this is done, we highlight who did the forms of labour that we decided were essential to the spirit of the project/paper. The people who did those forms of labour start to raise to the top. People who did multiple forms of these essential labours rise even further up. People who did less important work start to drop down. This always results in what we call “clusters” of people: all the people two did two essential forms of labour and several forms of other kind of labour are in one cluster; all the people who did one form of labour that wasn’t identified as stemming from the spirit of the project are in another.

The people in each cluster mean that we’ve decided their labour is commensurate. If someone(s) in a cluster did WAY MORE of a type of labour that their peers to the point that the group thinks it sets them apart, they change clusters.

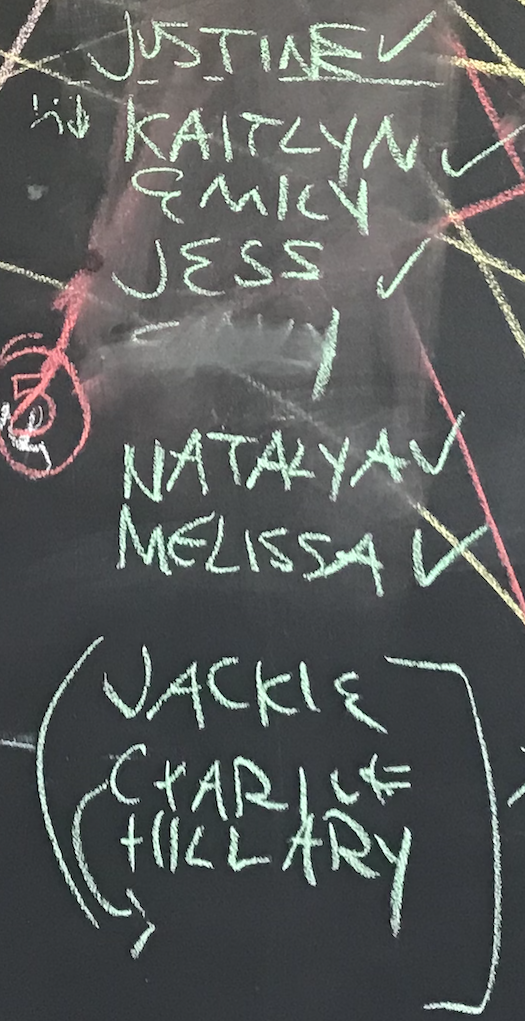

There are three clusters in this image. This means each person in the group did a similar amount and type(s) of labour. Sometimes this means that someone who did lots and lots of less crucial forms of labour will be clustered with someone who did one important type of labour. It really depends on how the collaboration went.

Often, the very bottom cluster can be people who might not be authors, but part of the acknowledgements. We distinguish an author as someone who is accountable to the paper. If it bombs and is deemed unethical, who is accountable? If someone walked up to someone on the author list and said “congrats on the new pub!” would that person know what they were talking about? All authors have to have read the paper and consented to be on it (this is the last step).

Step 5: Ranking within the clusters

Since the people in each cluster have been determined to be commensurate in terms of labour, there should be no more recourse to using labour (amount, type, etc) to rank people. “All things being equal” (as the phrase goes) in terms of labour, how else can we determine a linear author order? This is where we turn to equity. We start to consider social location, the different social markers associated with oppression and privilege for different groups of people). Magically, women, people of colour, Indigenous peoples, people from the Global South, people with disabilities, junior researchers, people who are introverts or shy, and queers get less credit for their ideas and labour, including in research. Here’s a place to address that directly. We cannot change the structure of which social markers tend to be oppressed or privileged in and outside of STEM, but we can be accountable to not replicating those in our spaces.

For us, it becomes important to differentiate between individuals and the groups they are interpolated into (meaning the social, cultural, gendered, racialized, educational, and other categories others put them in and treat them accordingly). For instance, someone may have specifically chosen not to pursue a PhD, but they are still in a privileged place as someone who could have applied for a PhD because they have a master’s degree. Some of the social location categories we’ve considered include:

- Race

- Indignity

- Gender

- Educational status, including whether the author is an academic or not and so more or less likely to be externally recognized as a researcher or not

- Disability

- Junior or senior status (e.g. Assistant professors vs full professors)

- Elder status (Elders always go first if they want to)

“Anchor author,” or last author, is sometimes recognized as an important and special place in author order in terms of getting extra credit/capital for being a mentor. But sometimes not. Whether we have an anchor author is based on the publication and the field the proposed anchor is working in–will they actually get more credit, or are they just last?

Step 6: Final review and consensus

Each of these steps end with consensus. The final step is to circulate the complete paper with the author order to all authors, including any that may not have been at the meeting, and receive written consent that they agree to the order. Then, we can submit the paper for publication. For many of us that collaborate with other groups, this is the step where we often see our name in an author list for the first time. For us, it’s the very last step.

These are not hard and fast rules, and we’ve developed this process over many years. For the most part, we look forward to these meetings and have a lot of fun. For more details on the process, see our paper on our

A request: We’ve heard that a lot of people use or adapt this method for their own research spaces. That’s fantastic. Please cite our paper (Equity in Author Order Protocol: A Feminist Lab’s Approach) as the methodological precedent of your process, ideally in your methods section/discussion of your methods, though in your acknowledgements is also fine if your discipline requires it. We find that for some reason, our intellectual labour on author order isn’t cited even when people tell us they used the protocol. See our citational politics project, too.

11 Comments

Comments are closed.