Being a scientist means taking sides…

Marine biologist Mary O’Brien says that, “once you’re a scientist, which means as soon as you systematically ask questions about the universe, you take a political side” (1993: 706). These politics happen in ways that seem harmless, but have far reaching effects: you ask some questions and not others (“how much plastics do cod eat, and how does this affect their health?” versus “how much plastic can a cod ingest before mortality occurs?”); we choose to work with some kinds of people and not others (students, community groups, industries, no one); we choose how we work with them (collaboratively, on contract, in solidarity); even the types of measurements we use are political (risk analysis that seeks a threshold of acceptable harm versus assessments based in the precautionary principle and effects at trace doses). In short, creating knowledge is a political act where some values and interests are reproduced and others are not. There is no way around this. We can only be more or less intentional in these choices.

CLEAR aims to make these decisions carefully and transparently based on our values and ethics. All research starts somewhere; in the words of biologist-turned-social-scientist Donna Haraway, all knowledge is “situated” (Haraway 1988). This situation includes the culture the research is situated in, as well as what Shawn Wilson calls a researcher’s axiology (morals, values, and ethics). Your axiology will determine the types of research questions that seem important and viable, the types of methods that seem appropriate and valid, and the types of research dissemination that are best. For Wilson, as for our lab, our axiology is based on accountability to relationships with other people, to the environment, and to other lab members: “For researchers to be accountable to all our relations, we must make careful choices in our selection of topics, methods of data collection, forms of analysis and finally in the way we present information” (Wilson 2008). Thus, in every step of our scientific process, we aim to be in good relations with land and the wider environment, work with humility and recognize the limits to our own knowledge and methods, and to be accountable to the communities who our research effects the most.

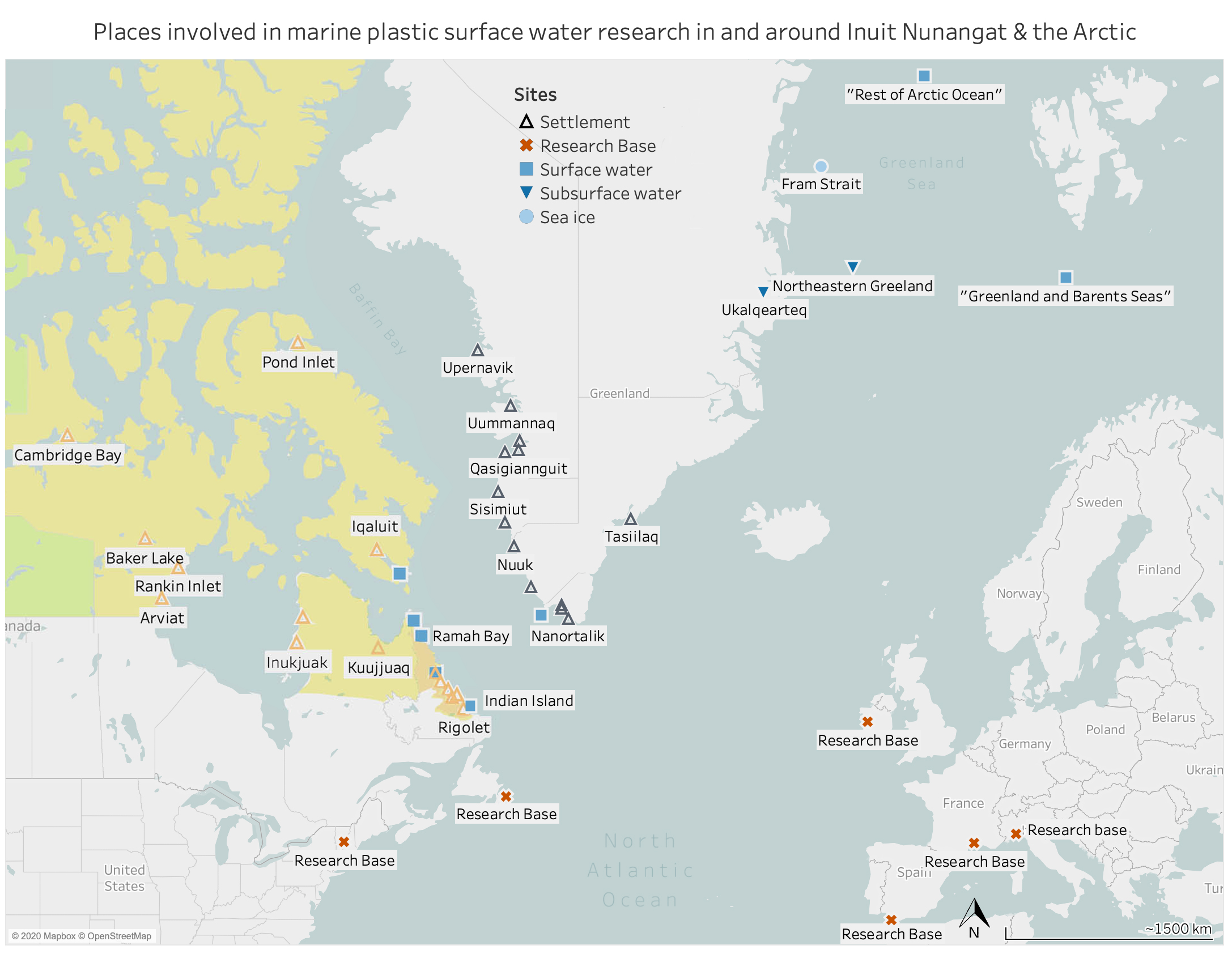

(Inuit Nunangat),” a paper under review. The map shows places associated with marine surface water plastic research in the Eastern Arctic, including research sites, researcher home bases for first authors on published research on plastics in water in the region, and settlements in homelands. Inuit Nunangat (Inuit homelands) is coloured for reference with different regions of Inuit Nunangat in different shades (Nunatsiavut in orange, Nunavut in yellow, and Nunavik in green), and settlements in Inuit Nunangat are coloured orange. The map shows a clear trend of researchers from the south producing all research in the north germane to the study of plastics in Arctic waters.

A lot of research is colonial, and we work to change those relations. Colonialism is not just about taking Land, though it certainly includes taking Land. Yellowknives Dene political scientist Glen Coulthard argues that colonialism is a way to describe relations characterized by domination that keeps land available for settler goals, that gives settlers “ongoing access to land as resource” (Coulthard 2014). These relations include the type of knowledge that is valued (like Western science), the type of knowledge that is extracted for that value (like Indigenous knowledge), the type of relationships with Land and the environment that are privileged (like resource management), the forms of settler laws and regulations that uphold these (like private property), what is taught in schools and how (such as the exclusion of Indigenous thinkers or teaching in English). The list is long. Colonialism is ongoing rather than historical. Colonialism is a set of specific, structured relations that allow these events to occur, make sense, and seem normal (to some). CLEAR’s lab book contains “a wee primer on colonialism” to help orient lab members to what colonialism is—and isn’t.

Anti-colonialism is a way to describe land relations in opposition to these systems, practices, and values. In science, it means working in a way that does not assume settler and colonial access to Indigenous land for settler and colonial goals, even when those goals are benevolent, well-intentioned, or environmental (see the primer for more). We understand that Western science is only one way to understand the world, and it is not the only way or the best way. We say anti-colonial science instead of decolonial science for many reasons, but mainly because we want to be specific about what we are up to, and what we are not up to; we agree with Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang when they say that decolonization, as the undoing of colonialism, is about returning Land to Indigenous peoples; decolonization is “the repatriation of Indigenous land and life; it is not a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools” like inclusion, consent, humility, solidarity, and reciprocity, all of which are good things but do not necessarily change oppressive land relations (2012, 1). We aim to identify and counter colonial values, concepts, and structures within science and the university through how we do everyday science with the final goal of doing science differently. There are many ways to do anti-colonial science. Some of our techniques include:

- Our guidelines for working with Indigenous groups

- Community peer review

- Rematriating samples (bringing them back to the Land, or under the control of Indigenous governance)

- Co-creation and use of Indigenous data sovereignty contracts

- Ensuring our methods, equipment, knowledge, and grant money stays with the Indigenous groups we work with so we are not needed for future projects (though of course we can be invited back)

See our lab book for more.

Other anticolonial labs

We are not alone! Here are a few Indigenous- and BIPOC led labs or research spaces that also do the constant, difficult work of changing colonial relationships in research. This list is not complete by any means, but reflects the labs that we know of, that have an online presence, and strong position statements that tell us about their leadership and methods. Labs or lab leadership that CLEAR has worked and can vouch for are noted with a *

- The Technoscience Research Unit:* University of Toronto, led by Dr. Michelle Murphy (Métis): The TRU draws together social justice approaches to Science and Technology Studies from across the university with an emphasis on Indigenous, feminist, queer, environmental, anti-racist and anti-colonial scholarship.

- The Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance,* based in Arizona: The Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance develops research, policy, and practice innovations for Indigenous data sovereignty.

- Indigenous Land & Data Stewards Lab*: The Indigenous Land and Data Stewards Lab is an interdisciplinary research lab supporting Indigenous and community-based natural resource stewardship. Our research works to better understand and apply local and Indigenous knowledge and governance systems in natural resources focused research and education.

- Tkaronto Circle Lab*: Located in Tkaronto, the Collaborative Indigenous Research Communities Land and Education (CIRCLE) Lab is a collaborative research lab based in Indigenous feminist ethics.

- WAMPUM Lab:* The WAMPUM Lab is oriented around Indigenous Ocean, Climate, Water Sustainability and Justice.

- Native BioData Consortium*, South Dakota: Revolutionizing Indigenous genomics and data sovereignty to decolonize health and environmental research.

- RELAB*: Based at the University of Alberta Faculty of Native Studies, the RELAB is comprised of faculty, students, and other creative workers who undertake “research-creation” projects grounded in making “good relations.” That is, we combine research with performance and other creative works to help decolonize sexualities, environments, and other sets of relations.

- The Summer internship for INdigenous peoples in Genomics (SING)* International Consortium, multiple locations (Canada, USA, Australia, Aotearoa).

- Critical Design Lab*: Critical Design Lab is a multi-disciplinary arts and design collaborative centered in disability culture and crip technoscience

- Geographic Indigenous Futures Collaboratory (GIF lab): The Geographic Indigenous Futures Collaboratory will focus on conducting geographical-based research with Indigenous communities globally with an eye toward promoting political, cultural, and climate-based futures for these communities in an era of climate crisis.

- Access in the Making Lab (AIM): AIM is an anti-colonial, anti-ableist, feminist research lab working on issues of access, disability, environment and care through creative experimentation

- Urban Theory Africa-Doing (UTA-Do): UTA-Do is a yearly critical urban studies ‘summer school’ that builds on the brash, daring, dynamic ‘uta-do’ mentality of Nairobi, where the program was first launched.

- Afro-Diasporas Futures in Education Collective: The Afro-Diasporas Futures in Education Collective is a mobile incubator that convenes a series of events to initiate and sustain transnational dialogues on the ways in which education research and practice in Canada and Australia can be enriched by Black studies scholarship.

- Bawaka Collective: The Bawaka Collective is an Indigenous and non-Indigenous, human-more-than-human research collective.

- Black Feminism Remix Lab: The Black Feminism Remix Lab aims to examine the past and present of Black feminism in Europe and how Black feminist activists are organising and mobilising today.

- Center for Indigenous Fisheries (UBC): At the Centre for Indigenous Fisheries (CIF), we re- imagine traditional “lab’ dynamics to build a community of Indigenous scholars and allies that place the needs and interests of Indigenous Peoples at the heart of all that we do. Grounded in this core commitment to conducting collaborative, just science, we aim to engage in and restore healthy relations between fish, people, and place.

- Chaudhary Ecology Lab: Research in the Chaudhary Lab examines fundamental questions in plant-soil-microbial ecology, plant microbiome functioning, and the emerging field of microbial movement ecology. We use trait-based approaches to develop predictive frameworks for microbial dispersal, community assembly, and biogeography with a focus on plant-fungal mycorrhizal symbioses.

- City as Platform Lab: The City as Platform project builds on theories developed by Dr. Beth Coleman, which explore how AI systems and algorithms are reshaping the design and function of the technologies that surround us, and the impact this has on our lives, our relationships with the built environment, and our rights as citizens.

- Diaspora Solidarities Lab (DSL): The Diaspora Solidarities Lab (DSL) is a multi-institutional Black feminist partnership that supports solidarity work in Black and Ethnic Studies conducted by undergraduates, graduate students, faculty members, and community partners who are committed to transformative justice and accountable to communities beyond the Western academy.

- Indigenous Foods Knowledges Network (IFKN): The goal of IFKN is to develop a network comprised of Indigenous leaders, community practitioners, and scholars (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) who are focused on research and community capacity related to food sovereignty and Indigenous Knowledge. The network seeks to build connections among Indigenous communities in the Arctic and the US Southwest.

- Indigenous Futures Institute: The Indigenous Futures Institute (IFI) aims to recast the relationship between a legacy of unethical scientific practice and Indigenous peoples. By creating pathways toward participatory science through design-thinking, IFI brings together global Indigenous communities to study, access, and harness science and technology, critically intervene in the production of knowledge, and dream up abundant and plentiful Indigenous futures in an age of climate crisis, global pandemics, and the continued denial of Indigenous sovereignty.

- Indigenous Mutual Aid: Indigenous Mutual Aid is an information and support network with an anti-colonial and anti-capitalist framework. We exist to inspire and empower autonomous Indigenous relief organizing in response to COVID-19.

- Indigi Lab: We want to create a future where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are leading in science, technology and digital innovation.

- SKC Indigenous Research Center, Salish Kootenai College: The IRC works toward the goal of advancing an Indigenous Research Methodology (IRM) for STEM to produce new knowledge and application of methods for the perpetuation and prosperity of Tribal College institutions and their respective local communities’ unique worldviews.

- Te Koronga: Te Koronga is a M?ori research excellence kaupapa based at the University of Otago. Te Koronga is comprised of: Te Koronga: Indigenous Science Research Theme and Te Koronga: Graduate Research Excellence Programme.

- Te R? Rangahau: The M?ori Research Laboratory, University of Canterbury: supports the advancement of Indigenous postgraduates in the College and advances research that is responsive to M?ori and Indigenous needs and aspirations.

- The Food Sovereignty Lab: The Food Sovereignty Lab is an interdisciplinary, collaborative effort that is student-designed and community-informed. To fully understand food sovereignty, one must understand the history of the impacts of colonization on the Indigenous nations of this region.

- Learning in Places, Washington Bothelll Goodlad Institute, led by Megan Bang: We co-design innovative research and practice with educators, families, and community partners that cultivates equitable, culturally based, socio-ecological systems learning and sustainable decision-making utilizing “field based” science education in outdoor places, including gardens, for children in Kindergarten to 3rd grade and their families.

- Ziibiing Lab: Ziibiing Lab is an Indigenous-led research collaboratory focusing on Indigenous politics in unique global, international, and transnational perspectives.

Further reading

- Cajete, G. (2000). Native science: Natural laws of interdependence. Clear Light Pub.

- Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. Minnesota Press.O’Brien, M. H. (1993). Being a scientist means taking sides. BioScience, 43(10), 706-708.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist studies, 14(3), 575-599.

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.

- Liboiron, M. (2016). On Solidarity and Molecules (#MakeMuskratRight). Discard Studies. Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, education & society, 1(1).

- Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409-428.

8 Comments

Comments are closed.