CLEAR’s new review paper looks at the ways different author groups understand Indigenous “participation” in divergent ways, and what this does to how plastic pollution itself is understood.

“Review of participation of Indigenous peoples in plastics pollution governance,” by Max Liboiron and Riley Cotter was commissioned for the new journal Cambridge Prisms: Plastics in the context of the new UN Plastics Treaty. While calls for Indigenous participation in plastics pollution governance are increasingly common, including those associated with the Treaty, exactly what participation means remains unclear. Our review of 70 texts (roughly half of which were peer-reviewed and a third of which were non-governmental or intergovernmental organizations) showed some clear trends.

First, we found that “participation” ranged greatly, from “gathering data from Indigenous people” (traditional extraction relationships) to Indigenous-led decision-making. This range is clustered into three types:

- Inclusion: Indigenous people, representatives, or knowledge are added to existing processes or organizations.

- Rights and sovereignty: framed participation in terms of rightsholder status and & the right to Indigenous self-determination and self-governance; and

- Indigenous Environmental Justice (IEJ), which overlaps with rights and sovereignty but it also foregrounds Indigenous traditional, decolonial, anticolonial, and Indigenous theories, obligations, law, and cosmologies in land relations, including governance. IEJ almost always changed core understandings of how plastic pollution causes harm and what the forces behind it are. We cover these in detail in the last section of the paper.

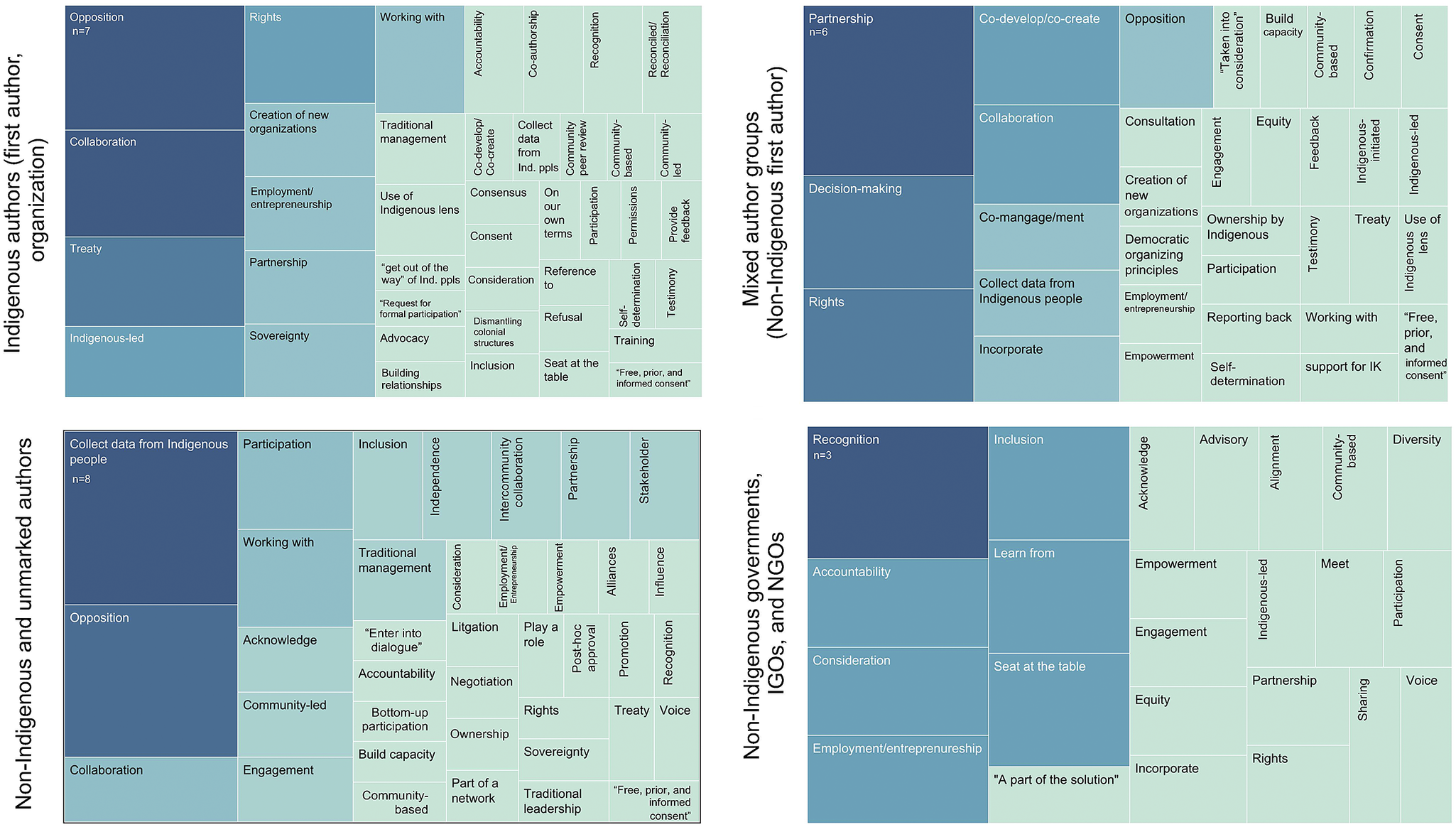

As we moved through our initial analysis, one thing really stood out: the author list of each text heavily determined the type of participation imagined and recommended. For instance, texts without Indigenous authorship advocated for inclusion, the most common of which was collecting data from Indigenous people. The diagram below shows the most common definitions or descriptors of Indigenous participation based on authorship.

Texts with one or two (usually one) Indigenous authors somewhere in the middle or end of the author list spoke of both involvement and rights, but we noticed that the core frameworks for talking about plastics didn’t shift to those used when Indigenous people were first authors. Nor did the type of participation advocated for (Indigenous decision-making, rights) extend to who was first author or contact author.

Texts with Indigenous first, solo, or team authors significantly shifted how plastics were characterized, moving from technological framings to Land relations and obligations, and linking colonialism to industry and policy, for instance. As scientists fluent in discussions on plastic pollution and environmental change, we find that Western, non-Indigenous, and elite research has overdetermined and restricted what plastic pollution is, and thus, how it might be governed. We conclude our review by outlining some of the characteristics of how plastic pollution is understood in texts that foreground an Indigenous Environmental Justice approach to the issue:

- Relationships first: Plastic pollution disturbs relationships and obligations

- Colonialism at the source: There are global trends of colonial power in plastic pollution

- Pollution, knowledge, and governance must be Place-based: Specificity and locality is essential in the face of global trends

- Problem definition is different for Indigenous communities: Community-based and holistic definitions of health and harm alter what counts as plastic pollution

- Holism matters: “Plastics” pollution includes a range of extraction, production, and disposal activities and related root causes

- Agents of a polluted status quo include the settler state and industry capture: complicating the science to policy pipeline

- There is a wariness of Western science and the call for more research

- Intersectionality matters: Attention to the intersections of indigeneity and other social locations, especially gender and generation

- Cultural resurgence is central to change: The role of plastic pollution interventions are evaluated in terms of their ability to strengthen cultural revitalization

- Togetherness is required for governance: Collectives, coalitions, partnerships, and sharing are required

The full paper is available free and open access here.