Ethics and principles of open source science tools

We have developed several open source tools for scientific study of plastic pollution. Open source means they are open, free (libre), and licensed as such, but also that materials to build them are lowest cost and easy to obtain whenever possible, they are able to be maintained and repaired readily. Our goal is to create more options for people to pursue research, both inside existing institutions (academia, NGOs, government, non-profit, start-up, business) and outside institutions altogether, diversifying the values and voices that research. We believe that open science hardware puts local knowledge in action and contributes to cognitive justice (the practice of many forms of knowledge and science). We are aligned with the goals of the Global Open Science Hardware (GOSH) movement, and CLEAR’s director, Dr. Max Liboiron, was a co-author of the GOSH manifesto that outlines these commitments.

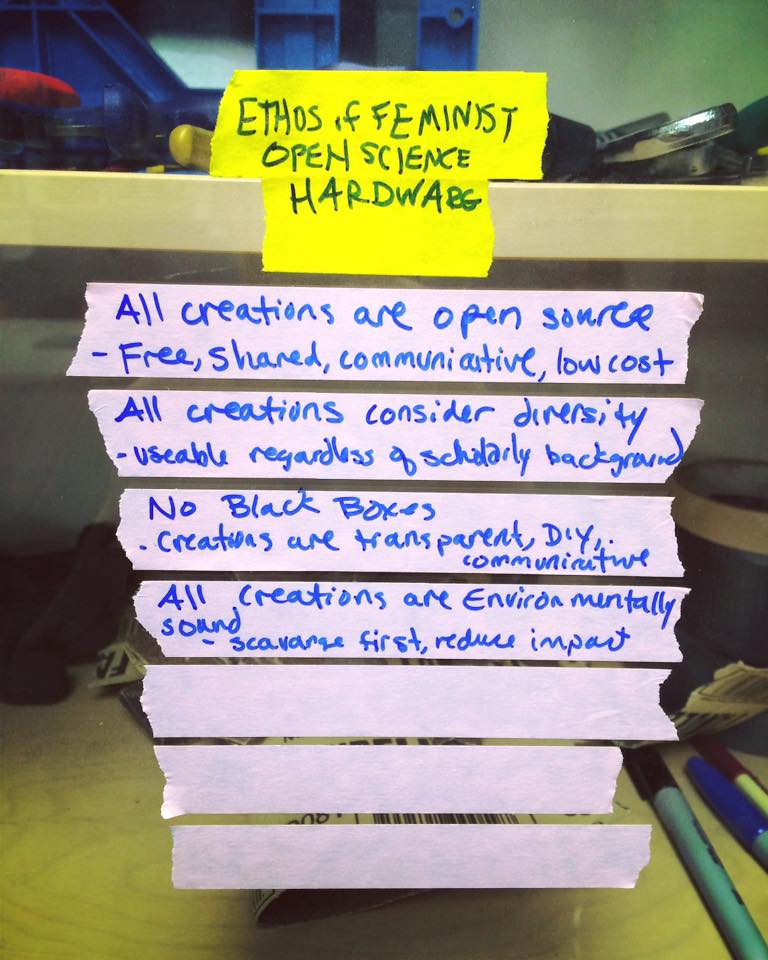

To that end, we have several guidelines for the creation of our open source tools, whether they are hardware or wetware:

- They are open sourced (free, shared, communicative, low cost) and licensed as such (usually via a CERN open hardware license)

- Inventions consider a diversity of users and environments, including being useable by those with different scholarly backgrounds, genders, sizes, and physical abilities

- We do not create black boxes, meaning that everything is documented in a transparent and communicative way that people can understand themselves

- Creations are environmentally sound, which can include scavenging for parts, eliminating parts or processes that are toxic, and ensuring repairability and reusability of parts

CLEAR open tools and protocols

We have developed several open source tools for scientific study of plastic pollution. These include the LADI trawl, a surface water trawl design costing about $500 that can be built with hand tools; and BabyLegs, a small-scale, DIY instrument made of soda pop bottles and baby tights that citizen scientists can use to monitor surface water. We are also developing a low cost, low toxicity design for digesting samples for microplastic analysis.

- BabyLegs (small, light, and inexpensive surface trawl for investigating the presence and types of plastics). Also see our post on Public Lab on BabyLegs.

- LADI trawl (larger surface trawl for being used behind a boat or ship for investigating densities and types of plastics)

- Ice Cream Scoop (surface trawl for kids that is easy to make for investigating the presence of plastics and other floating matter)

To support people in the use of these tools, we’ve also developed guides for how to use and analyze these tools and other processes involved in plastic pollution research. Often we’ve partnered with Public Lab to make these more accessible.

- Building BabyLegs

- How to use BabyLegs

- How to process microplastic samples from a trawl

- How to analyze collected plastics from a trawl

- How to analyze plastics forensically

- BabyLegs in the classroom

- How to collect guts for science

- How to analyze guts for plastics

We also support the use of other open science hardware and protocols that are not designed by us, including:

- Suite of DIY microscopes

- low-magnification “dissection microscope” for microplastics

- Marine Debris Tracker app (for researching shoreline plastics)

- Microplastic survey on sandy beaches

Open source at the university

Dr. Max Liboiron has written about efforts at keeping science hardware open source in a university setting (“Compromised Action: The Case of BabyLegs,” 2017), which includes tactics for maintaining open source creations in an institutional environment that favours or even mandates privatization. This is a direct quote from page 515-517 of that publication:

- Do not disclose. While our collective agreement states that we need to disclose inventions, there are two loopholes. One is the tyranny of common practice: most employees do not disclose. In a culture where this is normal, neglecting to disclose “might be” defensible. Secondly, and more concretely, the collective agreement at Memorial states that researchers shall disclose “the development or creation of any intellectual property that has potential for commercial exploitation.” If I did not think the IP had potential for commercial exploitation—which is not defined—then legally I did not have to disclose.

- Do not make commercially viable technology. For the research office, “viable” means that it can make back the considerable cost of obtaining a patent. Several of my students aimed to make their technologies cheap, transparent (meaning it was fairly obvious how it was made), and made of materials that included other patented items (like coffee filters).

- Disclose publicly. If you post your plans on a website, present them at a conference, or publish them in a journal, they are no longer private, and thus prevent a problem to privatization. The head administrator said that researchers accidentally disclose publicly all the time. Whoops!

- Do not sign required forms. Inventors will have to sign forms to hand over their IP rights. The lawyers said not to sign them. Alternatively, they recommended taking a long time to sign forms as a way to stretch out timelines and make them less efficient. I have begun filling out the wrong forms to add even more time to this process.

- Be difficult. One administrator noted that the process of creating jointly-owned patents requires a “coalition of cooperation.” If one (or more) people are not cooperating, the process falls apart.

- Invent with others, many others. Joint IP is more difficult to deal with because figuring out who has what original input into the object, and how much, and thus who must be involved in transferring IP and awarding payments is complicated, even prohibitively so. The more people that have been involved as co-inventors, the more complicated it becomes. Part of the reason is that IP is based on individualism, and if there are multiple people doing multiple tasks it becomes difficult to atomize which tasks are “assistant” tasks and which are “originating” tasks during the process of invention. This is amplified if some of those people are from outside of the university or outside the country given national differences in IP norms (Kranakis 2007, Merelis 2012).

- Work with students. Students are difficult to organize, particularly over the timelines that patenting can entail. As one administrator put it, “[t]hey disappear all the time! Especially after graduation.” At Memorial, there is also extra scrutiny of student-faculty shared IP because administration aims to protect students from having their IP controlled unfairly by faculty. Often, they just do not touch it.

- Use Creative Commons and other open licenses early and often. These licenses are quasilegal and it is not always clear where and when they are legally binding. Even if they are not binding in some areas, they still must be shifted through, which takes time and money.

- Do not invent technology––invent processes. While IP is supposed to cover proprietary technology and processes, the focus is almost exclusively on technology. CLEAR creates citizen scientific protocols as well instruments, and none of our protocols have ever been scrutinized, or even noticed. They certainly have not been disclosed (see point #1).