Ethnographies are a type of observational research that accounts for particular cultures and communities. At CLEAR, we use stories and ethnographies to investigate our own scientific culture and laboratory community, opening the ethical and social relations of science to investigation. We have an internal story and ethnography library where lab members write out experiences and memories from what they’ve done and learned in the lab. We incorporate stories and ethnographies into our lab book for teaching, into our research as evidence, and into film for understanding our methods and lab culture more broadly.

GUTS is a film directed by Taylor Hess and Noah Hutton (Couple3 Films) that shows how our research and our ethical commitments influence one another. We are working with Couple3 again on Laboratory Life, a project funded by MEOPAR that shows methodologies that are usually black boxed in science, including how author order is chosen for articles, how we run lab meetings, and how we facilitate a lab-wide commitment to specific shared values.

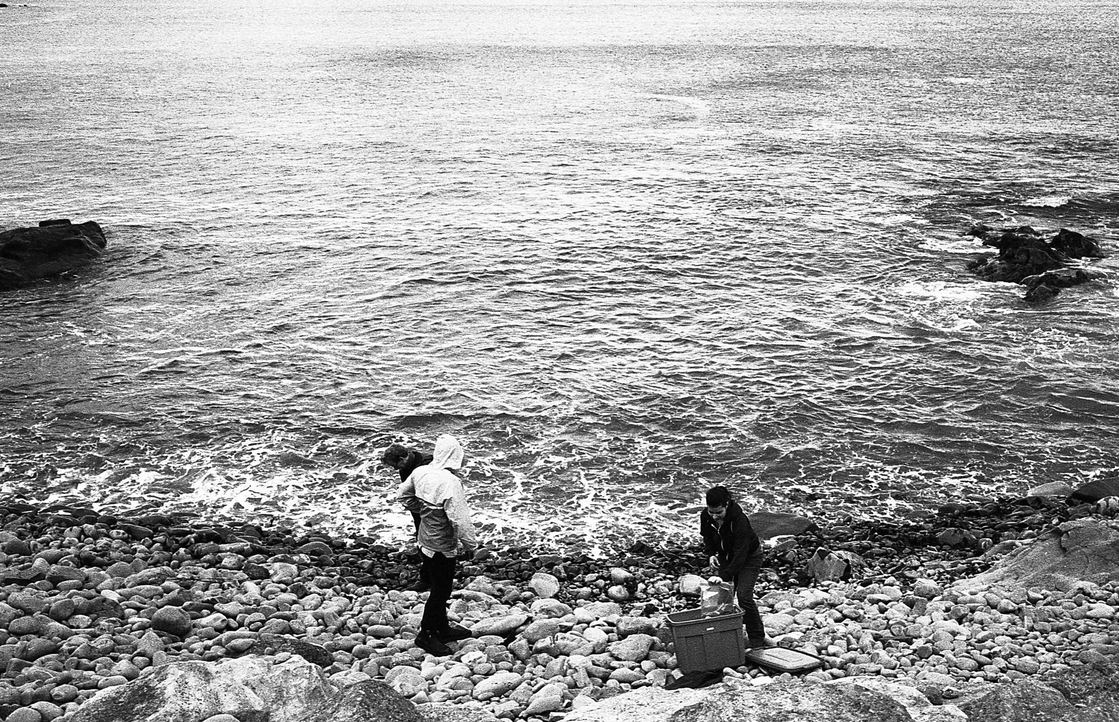

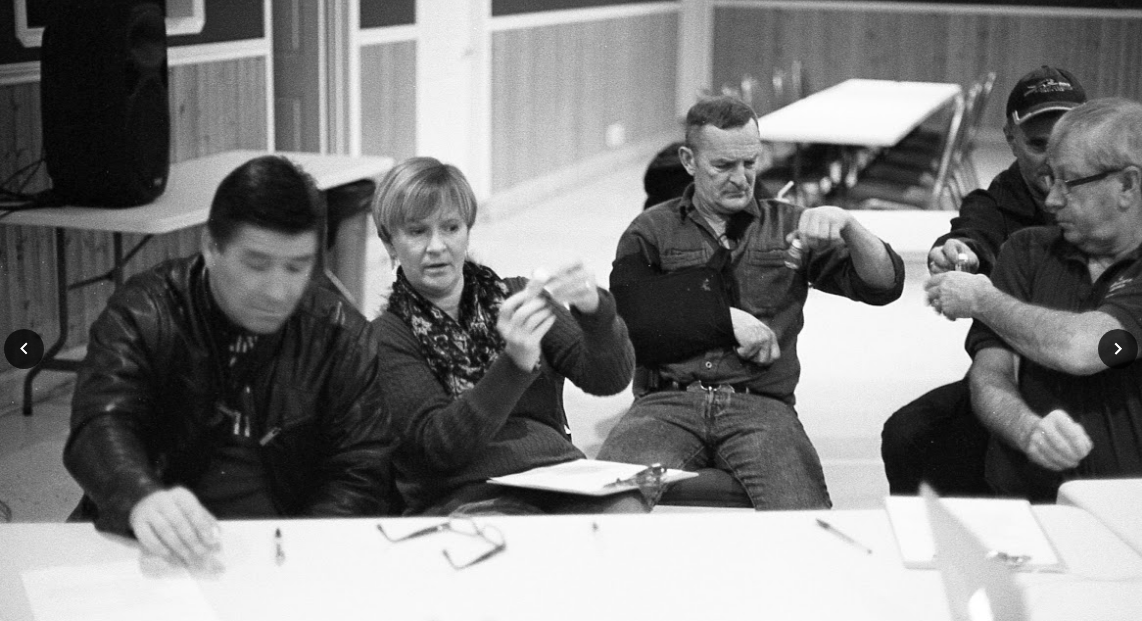

How we do science (2016-2018) is a photographic series by photographer-in-residence Bojan Fürst: “The idea behind the photographs is to engage with daily realities, to quote Stuart Franklin, of how science is done at least in this particular lab. To that end, as a photographer, I am working more closely with the researchers than I normally would in similar documentary projects. One of the ways we collaborate more closely is that the researchers play editorial and curatorial role for the project.”

Stories from our internal library have been used in two forthcoming research texts: “Doing Ethics with Cod” in Making & Doing (2021) and Pollution is Colonialism (2021). Here are two related stories about the same meeting to determine author order that appear in “Doing Ethics with Cod:”

I’m in the lab with fourteen other lab mates, seated around a table that’s topped with baked goods to nourish our bodies while our brains attempt to decide the author order of our newest plastic ingestion study with silver hake. We’re listing types of labor involved in the project so we can be sure to credit everyone who has been part of it. The list includes collection work gathering the fish, processing samples, writing, editing, organizing meetings, cleaning up, and grant administration. Now we’re adding another one. All fingertips reach skyward and wiggle: jazz hand consensus around the table. This is how we show agreement. We’ve all agreed that dying is a form of labor and it is worthy of a star—meaning it is among the most important forms of labor in this project. Labor means authorship credit. Max, who’s facilitating, adds “Fish” and a star-like scribble to the list of potential authors on the whiteboard, because fish are the ones who did the dying. I grab an extra granola cookie.

– E. Wells

The lab discusses putting the fish as first author. A lot of people are for that. People are excited, there is wiggling in seats. But then the tone changes. Charlie asks, “What relation are we setting up if we gift the fish authorship?” Nicole tells a story about being interviewed as a Newfoundlander for a book and how she would never want to be coauthor on that. Charlie tells a story of a professor who published a student’s term paper, and though the prof gave the student author credit, the student did not give consent to be published or be an author. Elise talks about how survivors elevate their cultural status by obituarizing the dead, using the names of the dead as capital. Taylor says, “Giving the fish author credit is in the spirit of the paper,” but as a group, we come to realize it is also wrong according to the lessons of the paper. “So,” I ask the group, “how do we want to credit the fish, then?”

– M. Liboiron

In 2021, we’re continuing our commitment to storytelling and ethnography with a dedicated, lab-wide project to hone our storytelling abilities so we can start telling stories as a collective to communicate our research. Stay tuned!