CLEAR is my lab, exactly in the tradition of professors in the sciences having labs to do their work, where professor and lab are synonymous. But instead of calling it Liboiron Lab (normal in the field), I called it something more descriptive of what it was. I get a lot of emails asking how I started the lab, how junior scholars might start labs, and how to transform existing labs into something more anticolonial, feminist, equitable, inclusive, etc. This post is going to outline how I/we did it in CLEAR with an eye to being general enough for other places. There is a video of a talk/Q&A from 2022, as well as a written outline based on FAQs. Welcome!

In Feb 2022, Dr. Nathan Matias, founder and director of the CItizens and Technology (CAT) Lab at Cornell, hosted me to talk about building community-oriented labs in universities. Here is the recording:

How did CLEAR start?

When I was a brand new professor in the social sciences, I decided that the lab model fit with my research agenda and ethics. I had co-founded and helped steer a mutual aid research collective that worked very much like a lab as a postdoc, called Superstorm Research Lab, and the lab model really worked for us.

It turns out that when you’re a professor, all you need to do is say you have a lab, and then you do. You need a name, a space (even if that’s just a website or a meeting room that you sign out once a week), at least one other person, and a declarative statement. That’s it. That’s enough.

Lab mission/vision/program: If you’re just starting, I highly recommend keeping your lab mission/vision general & flexible. Be ready to grow towards things you haven’t gotten to yet in 10, 15 years. For Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR) I choose “environmental action research” because that describes a lot of stuff. I wish I hadn’t chosen the word “civic,” but I was thinking a lot about civic science at the time, something I’m no longer concerned with (and have acute critiques of), but that’s the rub.

Lab name: IMHO, the best names for labs describe what they do: short & descriptive (ie. not CLEAR. Ha. But Northern EDGE lab, which studies the way treelines move north (or not) in climate change, or Data Warriors lab, which is all about how Indigenous peoples are using data to fight against colonialism, or Hackerteria, a platform for artists and biologists to make open art/science together… you get the gist). Google the name to make sure others don’t have the same name or variations on it. Check for a url that makes sense for the lab, especially if you’re going to do public work where people might have to remember the web address.

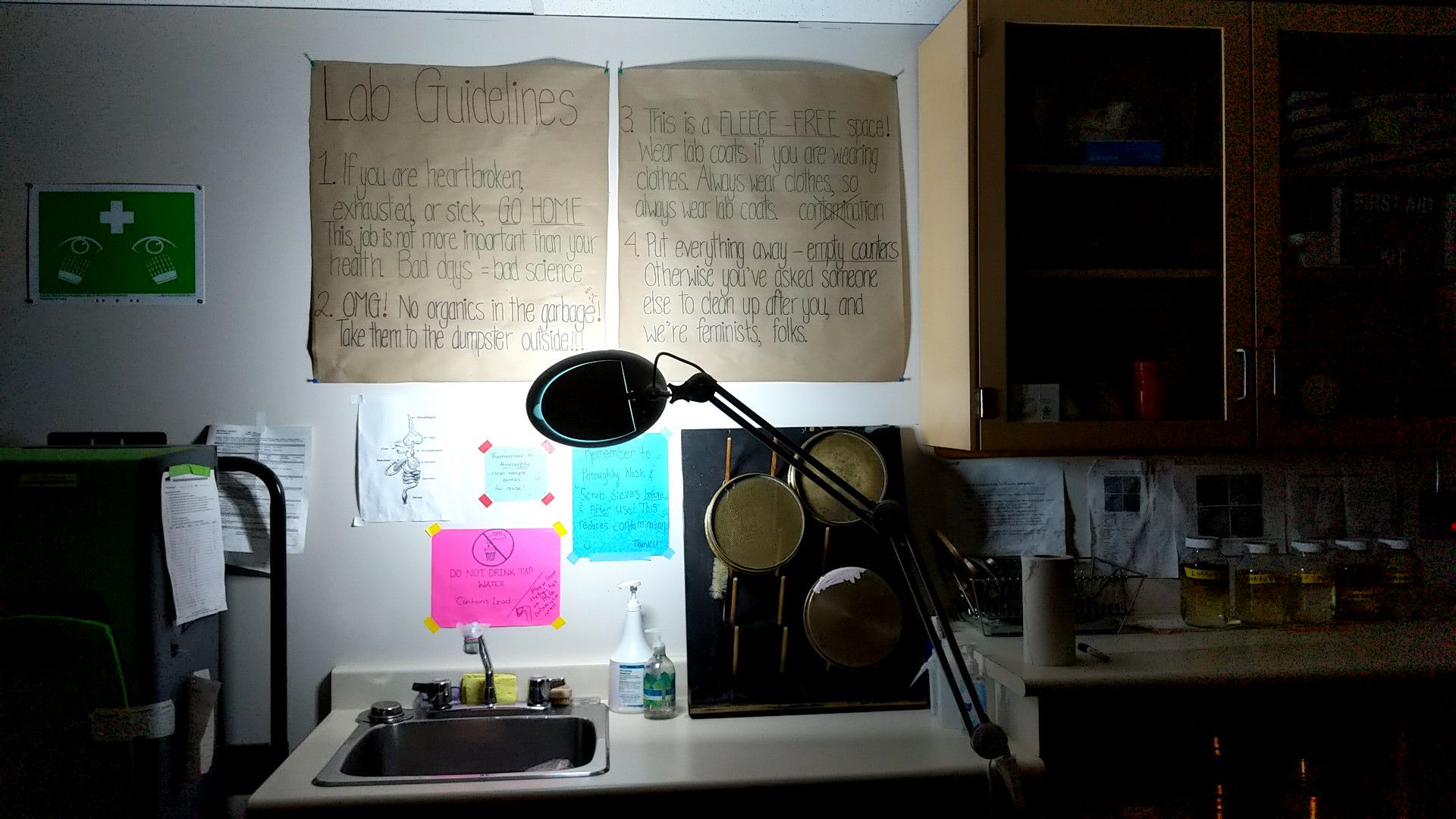

Lab space: If you can, negotiate for lab space when you get the job. I didn’t. When I arrived, my university (the dean) denied my request for space multiple times. But a colleague, Dr. Yolanda Wiersma, who was a full professor in the science department, had an extra storage room with a sink. She cleaned it out and loaned it to me. It was literally a closet and could really only fit one person at a time comfortably, but we did a few studies in this space while signing out various meeting rooms around campus for weekly lab meetings.

One day, The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC, the national media), did a story on my work. They tried to film our work in the little closet, and they had to stand on a chair in the hallway to get a not-awful shot. This shot showed the entire square footage of the closet, including the door tag that read, “storage.” It was on national television. Several faculty at the university texted the dean to voice their embarrassment. The next week, the university (faculty of HSS) found us a real lab space. After that, we also found out there’s a university form to fill out a formal request for space. That would have been the place to start.

Structuring the lab

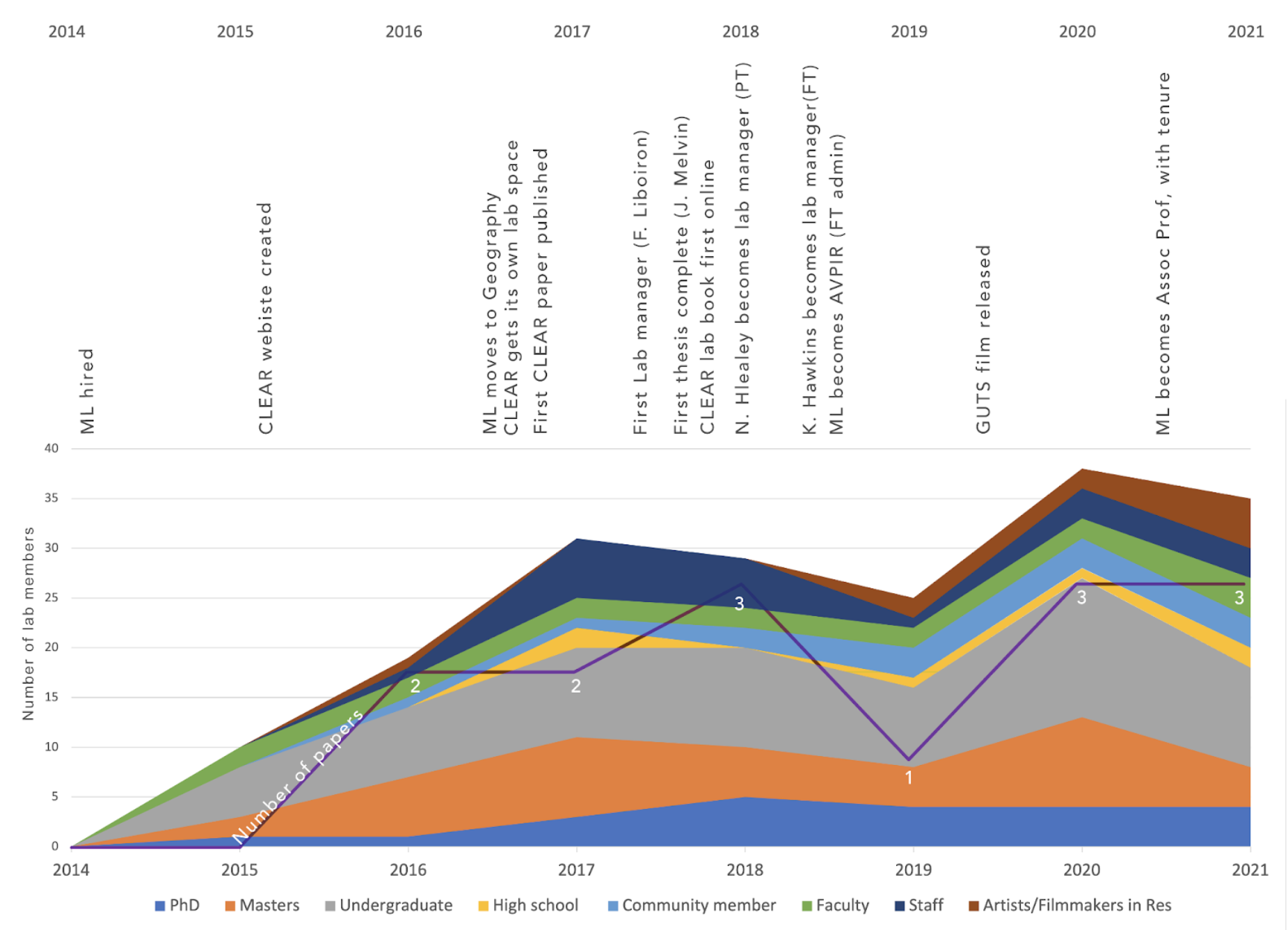

At the moment, CLEAR has about 30 people in it. It’s an unusually large lab. That’s different than a lab made up entirely of your graduate students (3-4 people). A lab at a university is very much a mentoring space, not just (or even primarily) a work space. So think about your style of mentoring and teaching and the structure that best reflects that. Bigger is not better. In fact, CLEAR is usually too big and I keep trying to make it smaller. Having 30 people talk in a lab meeting is not easy.

CLEAR is mostly undergraduate students and graduate students who aren’t “mine” (Research Assistants). I like this style of mentorship, and it’s the only way to have a significant number of Indigenous students in the lab. It also means we have a lot of folks who are there for a semester or two, while others stay with us for their undergraduate then graduate degrees. If I do get a student that is “mine” (my grants pay their stipends and I’m their chair), it’s not guaranteed that they’re also part of CLEAR, though this is almost always the case (see the section below on the social world of the lab).

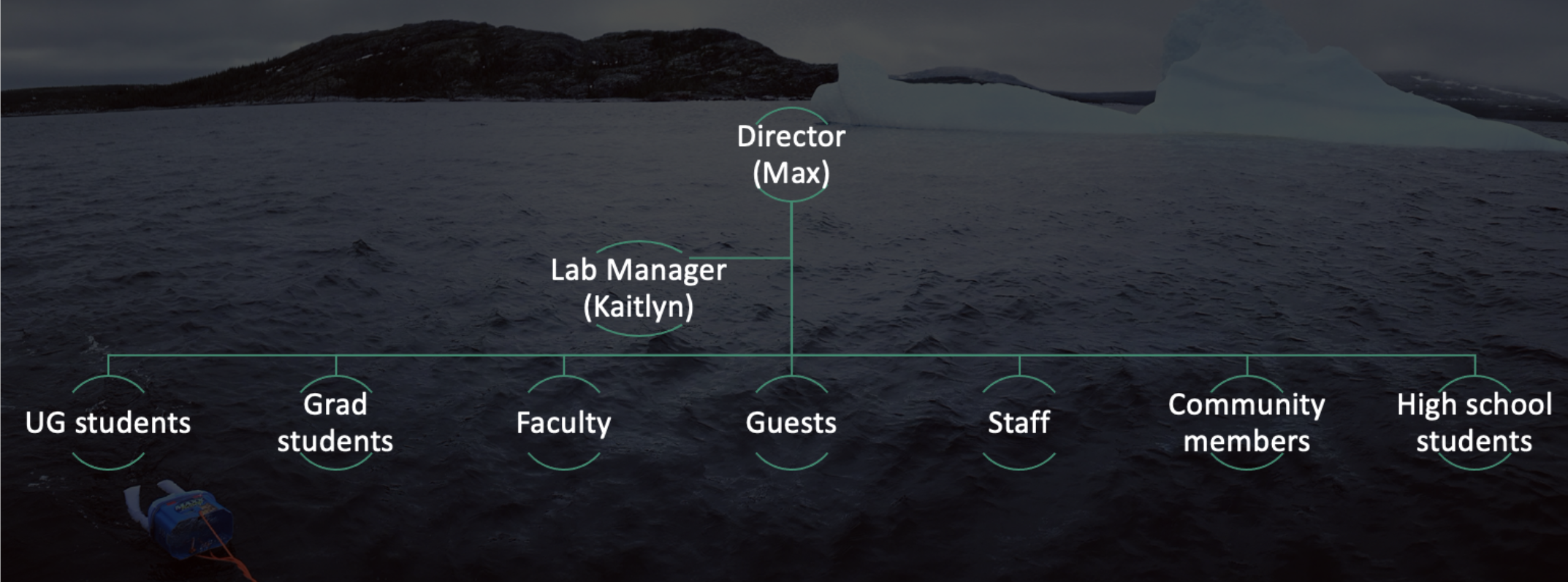

Sometimes people forget CLEAR is my lab because it’s not called Liboiron Lab. But it is mine in the tradition of natural science labs, and that’s important in terms of power, accountability, governance, and operations. I direct the lab and am accountable for everything it does. CLEAR also has a full-time (used to be part-time) lab manager, which is necessary when we have 20+ members. The lab manager does timesheets for employment, quality assurance and control on projects, most training (for bench science, lit reviews, onboarding, etc), looks after supplies, shipping, and is the first point of contact for all the logistical niggly wigglies for students, vendors, and university staff. They also do original research and get paid to do professional development. Every week, the lab manager and I meet to discuss how the lab is doing, what needs to be addressed or prioritized, and any issues that come up. We review hours together, project status, and if there are any interpersonal issues. We talk about any new or ongoing projects and the needs of those projects.

All other lab members are equal in terms of responsibility and decision-making. High school interns have the same amount of decision-making power as faculty. This is due to our consensus-based decision-making model, round robins, etc (see “How we Run a Lab meeting”). Not all decisions go to the lab to be made collectively. For instance, the lab manager and I are the only people involved in hiring. But each semester/year, the lab has a major project they do together (citational politics, storytelling, artists in residence program) and that is chosen as a group. Author order (see protocol on that), when lab meetings are, art/film projects on the lab, and other decisions are also decided collectively.

While Dr. Liboiron is involved in all projects in some way or another, and the lab manager is responsible for some of their logistics, there are many, many sub-projects going on at once and each has different lab members involved. Some lab members only come to lab meetings and are involved in the lab-wide project (e.g. citational politics, or the artist in residence program). Graduate students have their own projects, but often (almost always) other lab members are paid as RAs to help. Other projects have point people that are responsible for overseeing the project (often that person is Dr. Liboiron, but often not). Thus, every lab member is involved in one or more projects.

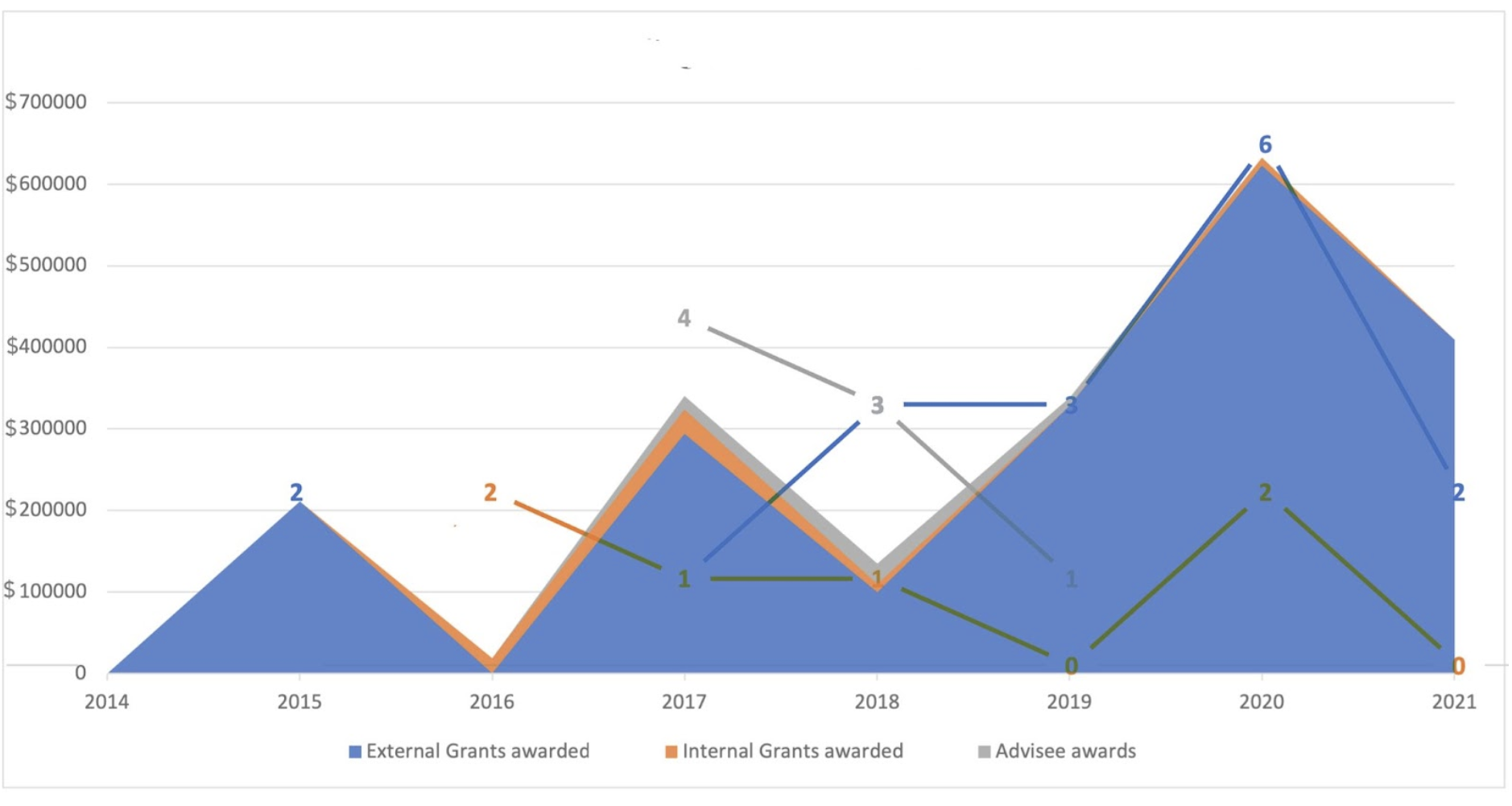

Funding: I have designed CLEAR so it can continue even if I miss 1 or 2 cycles of funding. With 20-25 people, the lab takes about ¾ of a million dollars to run every year, almost all of which is personnel (~90%–the largest share of which is the lab manager). The lab is also designed to shrink dramatically if we lose funding–mostly by losing personnel. We rent time on expensive equipment instead of buying our own so we don’t have to pay maintenance costs, and we often take contract work (where we don’t produce a paper at the end, only data for an outside party) so we can retain lab members (our fee structure includes payment for attending weekly lab meetings).

This graph shows one part of infrastructural and managerial labour: grants that keep the lab running. The filled in colour are the cash amount of grants in the year they were awarded (even though the money is spent over time–this is to show labour, not how much it takes to run the lab every year), and the lines indicate the number of grants. You can see that most of CLEAR’s funding has come from external sources and that a high number of grants does not necessarily correlate to a high amount of funding, especially in years with many internal and advisee grants, which tend to be much smaller.

We have a rule at CLEAR: all of CLEAR’s students are funded at or above union wages. No volunteers. I am firm on this. We do have other faculty in the lab, and they aren’t paid–their work in CLEAR is part of their salaried positions.

Personnel, aka your mentees and maybe your staff

Starting out: At first, I didn’t have funding for my own students. But other faculty routinely had research assistants they couldn’t train or have enough work for, or who were looking for extra projects. These generous colleagues gave me those funding lines, sometimes splitting their hours with me, sometimes donating their funding lines wholesale. I also asked around to get a few more. Gradually, as I learned how other faculty got students, I got my own funding lines for both research assistants and graduate students.

Indigenous lab members: I thought I’d have a lab of all-Indigenous lab members. Nope. Not particularly possible here at Memorial, given the number of Indigenous students, issues of relocation for graduate students, and not everyone wants to work on what we work on. While I do targetted hiring to ensure Indigenous people are processing samples from their own homelands (which I also write in as a funding requirement on grants), most of our Indigenous membership is remote (joins lab meetings via zoom).

Not sure where to advertise to get to Indigenous students? Then you’re probably not ready to retain them. Being very familiar with Indigenous communities on campus and in the region is the first step, not a middle step.

Number of lab members: Again, this depends on your mentoring style and how many people you can be accountable to. I can run a lab with 20-30 people because I have a full-time lab manager–all she does is be accountable to do the day-to-day running of the lab. If I didn’t have her, I’d likely have 4-5 members, tops.

Lab manager: I have a lab manager. At first I didn’t need one, but as I scaled up, especially with partner and community projects that require chasing down contracts, remembering invoice locations, training, and lots and lots of accountability, a lab manager became necessary for the ethics of that kind of work (for me). I cannot stress enough: a lab manager is amazing!!! That position has improved my quality of life and the life of the lab 50 fold, easily. Get a lab manager. This ties you into having to get funding to sustain a full-time staff member. It is worth it, no question.

If you get a lab manager, I recommend choosing them based on their alignment with your values and their ability to provide the culture you want in your lab. If that’s not there, other forms of competency don’t make up for it. You’ll end up with an efficient lab you don’t like very much.

Other faculty: As I developed the lab, I also invited in a couple of fellow faculty members who are still with us five years later. These faculty are not co-leads of the lab–they are lab members even though both are senior to my position. I specifically chose people who wouldn’t take over, who are good at stepping back and recognizing power relations, who are excited to be co-learners and who have the capacity to co-learn with undergraduates while also being co-mentors and allies to me when needed. I don’t actually recommend co-leading a lab with another faculty member. If you do want to go that way, I would only recommend doing it after you’ve worked together for at least a year in both a co-mentoring and co-research capacity.

Guest members: CLEAR did have guest members for a while– mostly virtual participants who came to all lab meetings but didn’t work on projects. These people weren’t paid, and it worked as a cultural exchange or a safe haven or a mentoring space for junior faculty or the basis of our Artist in Residence Program (in this case folks were paid). This was very valuable for them, and a lot of work for me and my lab manager. At the end of a semester, guests were either onboarded as full members or finished their time with us. I’m not sure what I think of this structure–it was a lot of work and really increases training and mentorship time.

Hiring: We’ve started having two people be part of hiring: myself and the lab manager. Having someone else is a good way to confirm or challenge initial impressions. CLEAR hires people who share our values, regardless of experience. We often take people with zero experience in our research area if they are humble, kind, accountable, and think in collective terms. This is what our interview process is about. Some of our interview questions are:

- Tell me a little about yourself, where you grew up, your connection to Land, and how you came to want to work in this area. [Note: this question is not “where are you from”, which is often used as a microaggression against people of colour, even if it’s also a normal way to ask Indigenous people about their relations and accountabilities]

- What do you know about CLEAR? How did you prepare for this interview?

- What made you want to work with us?

- What does feminism mean to you? What does anti-colonialism mean to you? (We don’t care about the “right” answer to these, so much as we care about how they’re dealt with. We know they’re real hard questions!)

- CLEAR operates as a collective, we work together on everything we do. What would you say are your greatest strengths in a collaborative setting? What collaborative skills would you be interested in learning or improving?

- Have you ever been involved in any activist or advocacy projects before, or any volunteer work? If so, can you talk about them a bit?

- Which kind of collaboration would you prefer:

- You consult with other scientists/community groups on a research question, work on the project independently and with full autonomy, then report back to them. You publish some papers from this as first author, and others as second author.

- You facilitate a research project with a community group where you basically work for them— you don’t have autonomy over the project, your main task is to give them resources and help build capacity where they say it’s needed. Your work does not get published, but the research is extremely useful to the community.

- You work in a lab on a lot of different projects. You aren’t the head of any of them, but you do a little here and there, getting middle or end author on a few papers, doing a variety of tasks and developing a lot of skills.

We tend to hire people who ask questions; make mistakes, own them, and move on; acknowledge other people and groups in their interview (while respecting their privacy if applicable); and who are self-reflexive and thoughtful. We tend not to hire people who are individualistic (including talking exclusively about how they will benefit from CLEAR), seem to be staking their identity or success on being part of CLEAR, who are not good at boundaries, who are not interested in working with others, or who interrupt the interviewer. We never hire people who may cause harm to others in the lab, which means we lookout for any signs of ableism, transphobia, sexism, and most subtly, lateral violence.

Facilitating the social world of the lab

This is probably the most important part of CLEAR: what makes CLEAR, CLEAR. I run CLEAR in a very specific way, based in our lab values, which are chosen collectively. I facilitate a collective rather than lead a collection of researchers. Our lab meetings are not about individual research projects, but about building up the collective. There are other models for labs, of course: apprenticeship, safer space, knowledge factory… these can overlap in different ways. But each will require a different set of structures, activities, accountabilities, etc.

The single most useful skill that I have is facilitation. In life, in lab, in teaching, in administration it has been a keystone of doing well. I highly recommend the AORTA Collective‘s training and documentation, but there are other groups that offer anti-oppressive facilitation as well.

Social problems: There will be massive social problems and you just have to deal with them. You will hire/accept a problematic/violent lab member at some point. Talk to your colleagues, own your responses, and stay with your values during conflict. That’s all you can do.

Documentation: Who is it that said, “documenting is a feminist practice?” They were totally right. A “regular” lab needs a lot of documentation: metadata, protocols, lists of people and what they worked on and their hours… projects pop in and out (unfinished projects languish) & you need that documentation! If you are also building a lab with a specific culture, then finding ways to document those ways will also matter. We have an apology protocol, for example. We write thank you notes to each other and staff the last lab of each semester.

Stopping: IMO, if the lab isn’t fun or flourishing, stop it. There was a period of time when the lab culture became unhealthy and I couldn’t turn it around. I closed CLEAR for a season (a summer) and started over. This involved the end of all hiring contracts and not renewing any staff. And no one seemed to notice. That’s drastic, but a lab isn’t an inherently good thing on its own. Feel free to not lab.

Techniques: CLEAR has published a set of its own practices, techniques, and protocols, but they’re all designed for us and our particular place, relations, and contexts. But they do have the ability to generalize in some ways. If you use these methods, please cite them in your work. They are part of our intellectual production.

- Choosing guiding values

- Equity in Author Order

- Running an Equitable Lab Meeting (basically, anti-oppresive facilitation and consensus-orientated decision making, plus pracitces for safer spaces)

- Citational politics

- Community peer review

- Protocols for guests to the lab

- Politics of data

- Accountability maps

- Guidelines for research with Indigenous groups

More are in our lab book. There are some other great lab books and resources out there for intentionally steering lab practices as well:

- Wreshler, Darren , Lori Emerson, and Jussi Parikka. (2021). The Lab Book: Situated Practices in Media Studies, University of Minnesota Press.

- D’ignazio, Catherine, and Lauren F. Klein. (2020). Data feminism. MIT Press.

- Livio, Maya, and Lori Emerson. (2019). “Towards Feminist Labs: Provocations for Collective Knowledge-Making.” The Critical Makers Reader:(Un) learning Technology: 286.

FAQ

Taken directly from my inbox:

- I am totally on board with this anticolonial science stuff, but I’m a PhD student, postdoc, or staff. I can’t run my own lab, though I’d like to. What do I do? As you may already know if you’ve been in your position for a while, the greatest supports for students, postdocs and staff are other students, postdocs and staff. While a PhD-becoming-postdoc, I co-founded the Superstorm Research Lab, a mutual aid research space. We didn’t have our own space, and we applied for funding as a group. Everyone still had their own thesis, dissertation, or book projects that their advisors over/determined, but we made a great space together to get that done. Everyone has some sort of jurisdiction where you have influence over social relations, whether it’s with your office mates, your cohort, people junior to you in a program, etc. You can start there, even as you try to influence social, cultural, and political relations outside of your jurisdiction. But without peers that support you and fill you up, you won’t be able to make change in other structures (IMHO).

- What is your educational background? How did you manuver the education system to end up like this? I left science as an undergrad to go into art. I have two art degress and my PhD is in Media, Culture, and Communication, where I studied plastic science from a social studies perspective (also called STS). I have one postdoc from Intel working on computational stuff and social relations, and another from an environmental health group dealing with social justice. I basically tacked through the system in directions that made the most sense at the time, and was never wed to a discipline. One of my main skills is being able to translate what I’m doing to other disciplines, spaces, and issues in ways that make sense and are useful to them.

- Do you get push back from the university? How do you deal with that? I don’t, really. I think there are a few reasons for this. First, I pass for white. That counts for a lot and I leverage it constantly. Second, I am successful by university metrics like number of publications, grant funding, etc. I adhere very closely to the collective agreement. Third, Memorial Univesrity’s culture and priorities suit my work: it supports community-based work, local problem sovling, hiring locals, good mentorship, and bringing in money and partners. Finally, I learned the hard way (or maybe just the long way) that university administration is not Evil or Assholey, but most admin genuinely care about the university community and I could easily meet them half way on that.

- How do you have time to do all this? 1. I have a lab manager. 2. I rest: I don’t work weekends or after 4pm, ever. This actually makes me much better at working. 3. I say no to a lot, a lot of things. 4. I don’t have children. 5. The lab structure allows mutual support and knowledge sharing so I don’t have to do most of the organzing, work, training, etc. 6. You never hear about the balls that drop. 🙂

- What, exactly is an anticolonial lab? Where do I learn about what that means? I wrote a chapter about this in my book Pollution is Colonialism. You can also read our lab primer on the topic and a one-pager I wrote for Nature Geoscience, “Decolonizing geoscience requires more than equity and inclusion” The very short answer: learn the ways your discipline and research benifits from non-Indigenous access to Indigenous land and replace those with better, more accoutable, land relations.

- How do I figure out how to guide our work according to anticolonial commitments? The first step is what we call “doing your homework.” Before you reach out to Indigenous groups, there are so, so many things we/they have created for you to read first! You can start with some of the texts above. I also reccomend:

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization is not a metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, education & society 1, no. 1 (2012).

- Tuck, Eve. “Suspending damage: A letter to communities.” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3 (2009): 409-428.

- Manuel, Arthur, and Grand Chief Ronald M. Derrickson. Unsettling Canada: A national wake-up call. Between the Lines, 2021.

- Vowel, Chelsea. Indigenous writes: A guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit issues in Canada. Portage & Main Press, 2016.

- FAQ on doing research in a good way, Memorial University

- How should I choose which Indigenous topics to work on? You don’t! Indigenous groups determine their own research priorities. See our guidelines for working with Indigenous groups. It took us four years to be invited to partner with our first Indigenous partner, even though we’re Indigenous-led. We did anticolonial work for years and gained a reputation for being in good relations. That was key to being invited.

- How do I attract Indigenous/queer/women/BIPOC/trans etc students? Until you can easily answer this question on your own, you shouldn’t. The ethical/justice/inclusion issue isn’t attracting underrepresetned students: it’s retaining them by supporting them to flourish on their terms. This means you have to understand what those supports would look like by knowing all about where those communities on campus, locally, and in the region.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.