By Domenica Lombeida, with Max Liboiron, Christina Marie Crespo, Alex Flynn, Kaitlyn Hawkins, Molly Rivers, and Riley Cotter

Introduction

Hello reader, my name is Domenica Lombeida. I am a non-binary Latinx 23-year old settler migrant from Ecuador living in the ancestral homelands of the Beothuk and Mik’maq. I am a lab member at the Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research. In CLEAR, one of our main goals is to do science differently in ways that align with our anti-colonial and feminist values. One of our most recent projects was to capture a way of citing against the norm, otherwise known as applying citational politics, to our publications. This blogpost is aiming to explain the ethical dilemmas that the project encountered: the tensions in classifications.

The final purpose of creating this project was to potentially have a protocol on how to cite, without relying on dominant science citation forms. The structure the collective decided on for the project was this: alter in different ways the citations of a few sections in one of our research papers that we chose. We named the different ways to alter the citation treatments and we split into groups and chose which treatment we wanted to be a part of. The process also included taking notes as a group and individually, some of which I will share in this post.

The final project had nine treatments in total (all relating to citing out of the norm for dominant science), but for the sake of simplicity and relevance to this piece, I will only explain three of them, all of which were categorized as the “Difference” group treatments. The three treatments were: increase gender diversity citations, racial citations, & global south citations. The method for each was to find relevant research within each category of treatment. For gender targets, it was replacing the overrepresentation of citations of men with more women, finding out how many women CLEAR already cites, finding non-binary/trans authors, etc; for racial targets, it was finding Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) authors, and for global south targets, it was finding anyone who belongs to the global south population, like South American authors. The alterations could take different forms, for example, replacing the citation, rewriting the sentence to refer to a new citation, or changing the context as to how we were referring to the citation (eg. stating an Indigenous author’s background instead of just plugging in the citation). Each member had to decide when a treatment was done, including what percentage of authors they wanted as a final citation target, and what their goal was in terms of their treatment.

It seemed easy at first: find another author who falls into the category of our treatment that has a study similar to what has already been cited. But several of us ran into multiple problems and fell down many rabbit holes while trying to do this. We also recorded and often shared our feelings and frustrations. We ran into a very similar problem: the dilemma of not knowing how to classify people.

Not knowing someone’s race, gender, or place of knowledge sometimes meant our goals for the treatments could never be completed, and it brought loads of uncomfortable feelings. There were tensions encountered while trying to complete a treatment, tensions that felt unresolved for most of us. To understand the tensions this process created and to overcome that, we need to look into classification systems.

Classification Systems

A classification system, as defined by Bowker & Star (1999), is a spatial, temporal, or spatio-temporal segmentation of the world. We live in a world where classifications are important to our understanding of the world–it is how we manage to organize ourselves and our surroundings. Classification systems are everywhere, including in our project and in the understanding of the treatments: how we defined racial categories, gender categories, and global south categories.

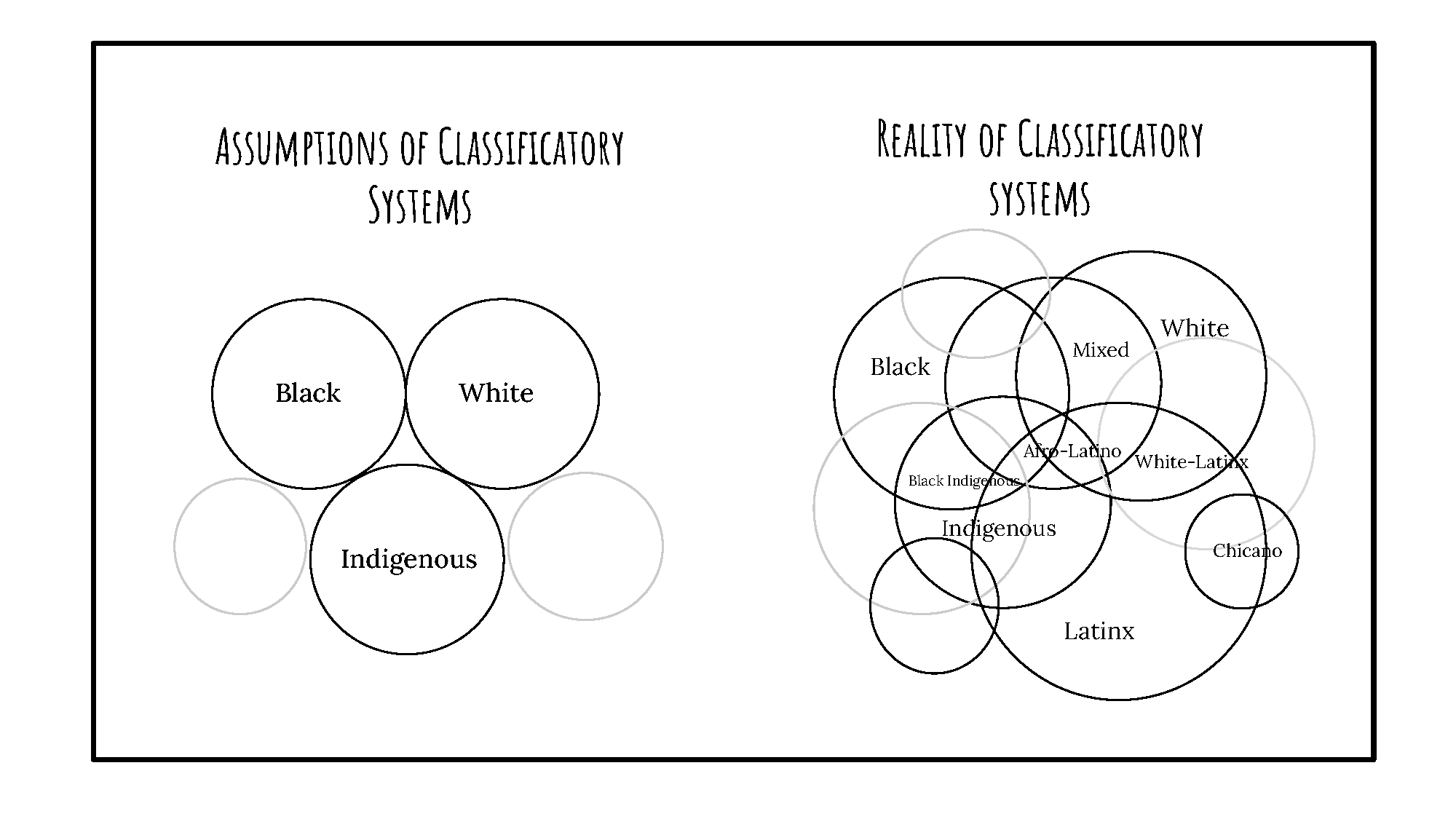

From Bowker & Star (1999), we understand that in theory, classification systems are designed to be consistent, complete, and the categories within them are mutually exclusive, but that they never work that way. So when we were classifying an author for a particular treatment, if we started with the assumption that there were perfect boxes which we could fit authors into, that assumption was challenged immediately. People’s classifications are not mutually exclusive, consistent, or complete. And there were what I will call “anomalies”, things that defy the set of rules within a classification system.

In the treatments, the assumptions of classificatory systems and anomalies looked like this: A lab member classifying authors for the category of “Global South” found themselves in a pickle trying to understand whether the author had to be born and doing their research in the Global South to be considered a ‘true’ Global South researcher. Here, the category of ‘Global south’ came with the assumption that there were already a set of rules to be able to fit into this category—even though we were the ones making the classification and assigning a meaning to it. The ‘anomaly’ to the ‘system’ of Global South treatment according to this set of rules would be all the researchers that were born and/or reside in the global north.

The ‘set of rules’ was the shocking thing about the treatments: There was a constant block when trying to classify because of our immediate unconscious act of assuming that the classifications themselves were complete and consistent. These assumptions were recognized as wrong and challenged immediately with great discomfort.

Now we understand that there is a tension of classification because of a set of rules. We can understand the ethical problems we encountered when trying to classify, which I will call: assumptions, the overclassification of categories, and the oppression tiers.

Describing the problem

“Problem: scientists often don’t disclose their positionality/identity in articles/personal websites…now what?

She looks pretty white… Damn it. Visual cues run deep.”

from Christina Crespo’s individual notes, with shared permission.

Here we encounter one of the rabbit holes of our progress in our treatments: There is discomfort when classifying when assuming visual cues to fit a classification. Visual cues play a big part in how we visually assume race. The classification of “race” in this case, has the set of rules (skin, name, other visual cues) that follow our assumptions on how to classify the person. But we had to challenge that assumption constantly, since we know that ‘race’ is not a classification that is complete, mutually exclusive or consistent. We could definitely be very wrong about a visual assumption we make. If you need any reassurance that that is true, Sorting things out (Bower & Starr, 1999) has a chapter (6) on the South African apartheid to talk about racial classifications and set of rules. This is true of any visual assumption – whether it be skin, nails, teeth, or names.

Determining if folks are from racialized groups is HARD. Much more difficult than trying to determine their gender, as it’s not obvious within a name alone (even though it can be difficult to tell gender within a name as well).

from Kaitlyn Hawkins’s treatment notes, shared with permission.

There are assumptions that are less ethically concerning to do: if a Black woman comes in the room, you will be able to say, “that is a Black femme”, but overall, having limited information on someone’s classifications does mean we have to assume – whether they are easy assumptions or not, they are uncomfortable decisions to make.

Things get more complicated when we challenge the mutual exclusiveness of categories in a classification. Just within race, things can get tricky. Figure 1 below describes what we expect out of classifying people based on racial background – when in reality there are a plethora of race categories and subcategories that can not be visible. Folks can be perceived in simplistic racial descriptors while having multitude of intersecting identities. These classifications may exist without our knowledge of them visually: Only if I wanted to read deeply into an author’s life history (and only if that information is publicly and easily available) would I find out that they are a North American resident with Latinx family.

When we also introduce other categories which, in current dominant culture, all humans come with: gender, sexual orientation, class, etc., we bring another confusing ethical question into the mix. This is an example of what that looked like in our treatments:

“Do we want to replace the citation with a global south researcher who is from the global south doing research in the global south, or do we want an author from Argentina who is white-passing and has had most of their education in the global north? Who had the most privilege to be in the place they are right now? Who is the most oppressed in academia?”

Treatment notes by author

This way of ranking people is what I call “Oppression tiers”: when we start putting oppression on a scale of worse or better off. If you are familiar with this action, you are aware it does not do anything other than hinder us and benefit those in power. It feels so unethical to be categorizing and ranking people’s oppression just to fit them into the true global south treatment.

These problems bring lots of ethical questions: Should we be digging deeper into an author’s history for tangible categories? Should we be designating classifications on authors that haven’t declared those classifications themselves? Should we be prioritizing certain classifications over others in our citational practices? Should we be visually assuming classifications?

Now that we know what classification systems are and the ethical questions we encountered when we were doing our treatments, we need to learn how to challenge the set of rules in order to move through citational politics with ethics. How do we change our perspective as to what a classification is to be able to include those that do not fit well into expected rules of that classification? How do we act consciously on our citational practices when including those not well represented in academia?

To understand how to challenge mutual exclusiveness, completeness and consistency of our classification practices, we should understand where these problems come from. I want to introduce to us two hopefully familiar terminologies: intersectionality and identity.

Understanding where the problem comes from

An important side-track: intersectionality and self-identity

Intersectionality is one way to think about multiple, competing, complex systems of power and how they come to bear on the incompleteness of classification. It is used as an analytical tool to understand the relationships between the systems of oppression (systemic racism, misogyny, colonialism, etc.) and how they come to bear on individuals and groups simultaneously (Collins and Bilge, 2020).

Intersectionality was coined by Black feminist scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, in part, to note where classifications assume mutual exclusiveness (you are a woman. You are Black. But you are not a Black woman). Kimberlé Crenshaw writes: “Although racism and sexism readily intersect in the lives of real people, they seldom do in feminist and antiracist practices. And so, when the practices expound identity as woman or person of colour as an either/or proposition, they relegate the identity of women of colour to a location that resists telling” (Crenshaw 1991: 1242).

Intersectional analysis presents a simple argument that classifications lack: the understanding that the ‘set of rules’ from a classification are created by power structures to oppress and marginalize people. Intersectional analysis allows us to see the power dynamics that currently exist and how they impact unevenly.

For this blog post, identity is, in simple terms, where each person sees themselves in terms of their own classification, whether it be gender, sexual orientation, race, etc. Because identity encompasses too many things outside the scope of my understanding and this blog post’s relevance, I am only talking about self-identification. Self-identity is formed out of a combination of all of these classifications, and shifts all the time. As chicana feminist queer author Gloria Anzaldua wrote: “It’s not race, gender, class, sexuality, or any single aspect of the self that determines identity but the interaction of all these aspects plus as yet unnamed features. We discover, uncover, create our identities as we interrelate with others and our alrededores/surroundings” (Anzaldua, 2015: 75).

Self-identity connects to intersectionality in many ways. Together, self-identity and intersectionality help us see why those problems we had classifying exist. It allows us to see the context of the power imbalances and how assumptions from classifications reduce or complicate self-identity. Let’s take a look at this quote:

“Then again, what if Patricia is actually non-binary, or Mark is a woman? If this is too complicated to tackle, is it simpler to just let it be? Is it fair for me to be forcefully trying to look for people’s genders?”

Treatment notes from author

Doing intersectional analysis of this means looking into the context of the academy to see the power imbalance. In the chapter, “Resistance Is Futile! You Will Be Assimilated: Gender and the Making of Scientists”, Indian biologist and social science author Banu Subramanian writes about scientific culture and its way of penalizing self-identity. She writes:

“Science need not attend to the experiences because it claims a ‘depersonalized and disembodied discourse’. Scientists’ individual identity does not matter because scientists are interchangeable, all independent nodes in the production of knowledge” (Subramaniam, 2014: 181).

Subramaniam also draws the relation this has on gender: “A woman would have to be trained in such a way as to render her gender identity invisible or always conflicted and difficult” (Subramaniam, 2014). This unfortunately means that women and BIPOC people in academia are taught to hide behind ‘neutral’ masculinity and whiteness (Subramaniam, 2014).

Dominant academia has a particular way of enforcing whiteness into its culture. As Girish Daswani, a CLEAR lab member, anthropologist and social scientist writes, “Whiteness is systemic and institutional and in plain sight but usually not recognized or simply denied by those who seek to replicate it” (#EOTalks 2, 2020).

Subramaniam’s intersectional analysis of the academy makes it clear that both systemic sexism and systemic racism in academia are what created a rejection of public classifications and public self-identity. When examining this context, we are able to understand that classifications and self-identities are hidden out of survival: Creating male pen names to survive in a systematically sexist racist academia to be able to be cited more is a form of protection.

There is much more to citational politics and its standard to reproduce white heteromasculinity than this previously explained section. I encourage you to read “Citation Matters” (Mott and Cockayne, 2017).

Mark, from the quote, could self-identify as a woman, but I’ll never know and I’ll have to make unfortunate assumptions to not cite when raising oppressed gender identities. Mark has the right to keep that identity to themselves and may do so out of fear of not getting cited in dominant academia.

Thinking about classifications, intersectionality and self-identity in relation to citational politics shows us that our hesitations when completing the treatments are valid and come from the systemic problems we are woven into. “Oppression tiers”, or the ranking of oppressions, are woven into our way of thinking from understanding that those who have intersecting oppressions are most affected by citational politics in academia. Our need to understand a person’s classifications to the fullest comes from the assumption that classifications should be easily explained, yet intersectionality teaches us that that is not true.

And finally, assuming someone’s race, gender, place of origin causes so much discomfort not just because we could be wrong. When we dig up people’s public information for their classifications, we could be raising self-identities that were not meant to be raised. We could be stepping over some ethical toes because people who are affected by the systems of oppression may not want their self-identities and classifications to be public.

When we can see that classifications and self-identities are hidden out of survival, and they are ever-changing, we can see that our fear of being wrong about someone’s classification goes beyond the repercussions that we have as authors. We could be raising old expired self-identities of folks, putting people in academic danger or ruining an self-identity they were curating. We could be doing a multitude of wrong things. What do we do now?

End thoughts

Reading about classifications and adding intersectional analysis and self-identity to me demonstrates that what we are doing here (citing out of the norm with values) works against us just because we are inside the systems we want to dismantle. As Chicana feminist author Gloria Anzaldua puts it: “Like immigrants, those in the academy find themselves constantly trafficking in different and often contradictory class and cultural locations; they find themselves in the cracks between the world” (Anzalua, 2015: 71). Doing citational politics and science otherwise means we need to push through concepts while we still live in them.

It also shows me that the way we wanted to do our treatments (carefully putting people in a “gender”, “race” and “location” box to cite for later) was not working and will probably only get us half way there. When we talk about self-identity, we can see that classifications are arbitrary in relation to self-identity because they are ever changing. But this does not mean that it is impossible to do citational politics without ethics. In my opinion, we need to find a way to move past classifications. Anzaldua writes: “We must unchain identity from meanings that can no longer contain it; we must move beyond externalized forms of social identity and location such as family, race, gender, sexuality, class, religion, nationality” (Anzaldua, 2015: 73).

Doing citations

So what now? I might not have concrete solutions on how to move in the right direction, but I have found some ways that keep us away from the harmful problems we keep encountering. Respecting self-identity when it is publicly available is a start. One way to do that is to look for positionality statements whenever possible. We avoid doing visual assumptions by allowing researchers to socially position themselves instead of us doing that work. Another way of respecting self-identity is finding collective research spaces that position their collective self-identity for organizing. Collective self-identification allows us to avoid digging into individual identities, and ranking them. There are plenty of collective research spaces that organize around their identities: 500 queer scientists, Indigenous health researchers database, and Cite Black Women to name a few.

Other than respecting self-identity, one must keep in mind that none of this work is simple, but we have to start somewhere. We need to challenge classificatory systems and create new ways to move forward while challenging those systems we are in, just like Gloria Anzaldua says: “When we adapt to cambio (change), we develop a new set of terms to identify with, new definitions of our academic disciplines and la facultad (the ability) to accommodate mutually exclusive, discontinuous and inconsistent worlds.” (Anzaldua, 2015: 79).

If positionality statements were common, and we didn’t have to constantly challenge the depersonalization of science discourse (which would require systems of oppression to disappear all of a sudden), all this would have been solved with barely any scratches. Easier said than done! We need to keep in mind that we have so many things to learn and unlearn and raising these ethical questions was a great start at classifying in citational politics with ethics. Good luck!

Acknowledgement: I want to thank Dr. Max Liboiron, Christina Crespo, Molly Rivers, Kaitlyn Hawkins, and Alex Flynn who reviewed, edited, and directed me in several parts of this blogpost. Without their help and minds, there wouldn’t be a blogpost.

References

- Anzaldúa, G. (2015). 4. Geographies of Selves—Reimagining Identity. In Light in the dark/Luz en lo oscuro (pp. 65-94). Duke University Press.

- Bowker, G., & Star, S. (1999). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences (Inside technology). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Everydayorientalism. (2020, July 29). #EOTalks 2 – the portraits on the wall: On the whiteness of academia by Girish Daswani. Everyday Orientalism. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://everydayorientalism.wordpress.com/2020/07/02/everyday-orientalism-talks-the-portraits-on-the-wall-on-the-whiteness-of-academia-by-girish-daswani/

- Hill Collins, P., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality (Second ed.).

- Mott, C. and Cockayne, D. (2017). Citation matters: mobilizing the politics of citation toward a practice of ‘conscientious engagement’. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(7), pp.954-973.

- Cite Black women. Cite Black Women. (n.d.). Retrieved October 2, 2021, from https://www.citxeblackwomencollective.org/.

- 500QS (n.d.) 500 Queer Scientists. https://500queerscientists.com/

- NCCIH (n.d.) Indigenous Health Researcher Database. https://www.nccih.ca/512/Indigenous_Health_Researchers.nccah

- Subramanian, B. (2014). “Resistance Is Futile! You Will Be Assimilated: Gender and the Making of Scientists.” Ghost Stories for Darwin: The Science of Variation and the Politics of Diversity. University of Illinois Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt6wr5ch

- Oppression olympics. Urban Dictionary. (n.d.). Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Oppression+Olympics

This piece is part of CLEAR’s Citational Politics working group. Our citational politics public Zotero library on key sources about the politics of citation can be found here. Other writing from the working group includes:

- Molly Rivers, Waking up to the politics of citation (2021)

- Kaitlyn Hawkins, The researchers that search engines make invisible (2021)

- Max Liboiron, Firsting in Research (2021)

- Max Liboiron, Citational Politics in Tight Places (2022)

- Alex Flynn, Catching an Authentic Lake Trout: Knowledge Legitimization in Academia (2022)

- Dome Lombeida, The mental tangles of classification (2023)

- Rui Liu, Citing toward Community, Citing against Harm (2023)

5 Comments

Comments are closed.